Resident Theologian

About the Blog

Tech for normies

On Monday The New Atlantis published my review essay of Andy Crouch’s new book, The Life We’re Looking For. The next day I wrote up a longish blog post responding to my friend Jeff Bilbro’s comment about the review, which saw a discrepancy between some of the critical questions I closed the essay with and an essay I wrote last year on Wendell Berry. Yesterday I wrote a seemingly unrelated post about the difference between radical churches (urban monastics, intentional communities, house churches, all to varying degrees partaking of the Hauerwasian or Yoderian style of ecclesiology) and what I called “church for normies.”

On Monday The New Atlantis published my review essay of Andy Crouch’s new book, The Life We’re Looking For. The next day I wrote up a longish blog post responding to my friend Jeff Bilbro’s comment about the review, which saw a discrepancy between some of the critical questions I closed the essay with and an essay I wrote last year on Wendell Berry. Yesterday I wrote a seemingly unrelated post about the difference between radical churches (urban monastics, intentional communities, house churches, all to varying degrees partaking of the Hauerwasian or Yoderian style of ecclesiology) and what I called “church for normies.”

That last post was of a piece with the first two, however, and provides some deep background to where I was coming from in answering some of Jeff and Andy’s questions. For readers who haven’t been keeping up with this torrent of words, my review of Andy’s book was extremely positive. The primary question it left me with, though, was (a) whether his beautiful vision of humane life in a technological world is possible, (b) whether, if it is possible, it is possible for any but the few, and (c) whether, however many it turns out to be possible for, it is liable to make a difference to any but those who take up the costly but life-giving challenge of enacting said vision—that is, whether it is likely or even possible to be an agent of change (slow or fast) in our common social and political and ecclesial life.

I admit that my stance evinces a despairing tone or even perspective. But let’s call it pessimistic for now. I’m pessimistic about the chances, here and now, for many or even any to embody the vision Andy lays out in his book—a vision I find heartening, inspiring, and apt to our needs and desires if we are to flourish as human beings in community.

Given my comments about church for normies yesterday, I thought I would write up one final post (“Ha! Final!” his readers, numbered in the dozens, exclaimed) summing up my thoughts on the topic and putting a pinch of nuance on some of my claims—not to say the rhetoric or metaphors will be any less feisty.

Here’s a stab at that summing up, in fourteen theses.

*

1. Digital technology is misunderstood if it is categorized as merely one more species of the larger genus “technology,” to which belong categories or terms like “tool,” “fire,” “wheel,” “writing,” “language,” “boat,” “airplane,” etc. It is a beast of its own, a whole new animal.

2. Digital technology is absolutely and almost ineffably pervasive in our lives. It is omnipresent. It has found its way into every nook and cranny of our homes and workplaces and spheres of leisure.

3. The ubiquity of Digital (hereafter capitalized as a power unto itself) is not limited to this or that sort of person, much less this or that class. It’s everywhere and pertains to everyone, certainly in our society but, now or very soon, in all societies.

4. Digital’s hegemony is neither neutral nor a matter of choice. It constitutes the warp and woof of the material conditions that make our lives possible. Daycares deploy it. Public schools feature it. Colleges make it essential. Rare is the job that does not depend on it. One does not choose to belong to the Domain of Digital. One belongs to it, today, by being born.

5. Digital is best understood, for Christians, as a principality and power. It is a seductive and agential force that lures and attracts, subdues and coopts the will. It makes us want what it wants. It addicts us. It redirects our desires. It captures and controls our attention. It wants, in a word, to eat us alive.

6. If the foregoing description is even partially true, then finding our way through the Age of Digital, as Christians or just as decent human beings, is not only an epochal and heretofore unfaced challenge. It entails the transformation of the very material conditions in which our lives consist. It is a matter, to repeat the word I use in my TNA review, of revolution. Anything short of that, so far as I can tell, is not rising to the level of the problem we face.

7. At least three implications follow. First, technological health is not and cannot be merely an individual choice. The individual, plainly put, is not strong enough. She will be overwhelmed. She will be defeated. (And even if she is not—if we imagine the proverbial saint moving to the desert with a few other hermits—then the exception proves the rule.)

8. Second, modest changes aren’t going to cut it. Sure, you can put your phone in grayscale; you can limit your “screen time” as you’re able; you can ask Freedom to block certain websites; you can discipline your social media usage or even deactivate your accounts. But we’re talking world-historical dominance here. Nor should we kid ourselves. Digital is still ruling my life whether or not I subscribe to two instead of six streaming platforms, whether or not I’m on my phone two hours instead of four every day, whether or not my kids play Nintendo Switch on the TV but not in handheld mode. Whenever we feel a measure of pride in these minor decisions, we should think of this scene:

Do we feel in charge? We are not.

9. Third, our households are not the world, and we live in the world, even if we hope not to be of it. Even if my household manages some kind of truce with the Prince of this Age—I refer to the titans of Silicon Valley—every member of my household departs daily from it and enters the world. We know who’s in charge there. In fact, if you don’t count time sleeping, the members of my own house live, week to week, more outside the home than they do inside it. Digital awaits them. It’s patient. It’ll do its work. Its bleak liturgies have all the time in the world. We just have to submit. And submit we do, every day.

10. But the truth is that the line between household and world runs through every home. We bring the world in with us through the front door. How could it be otherwise? Amazon’s listening ears and Netflix’s latest streamer and Google’s newest unread email and Spotify’s perfect algorithm—they’re all there, at home, in your pocket or on the mantle or in the living room, staring you down, calling your name, summoning and inquiring and inviting, even teaching. Their formative power is not out there. It’s in here. Every home I’ve ever entered, It was there, whose name is Legion, the household gods duly honored and made welcome.

11. Jeff rightly pushed back on this “everyone” and “everywhere” line in my earlier post. I should be clear that I’m not exaggerating: while I have read of folks who don’t have TVs or video games or tablets or smartphones or wireless internet, I haven’t personally met any. But I allow that some exist. This means that, to some extent, tech-wise living is possible. But for whom? For how many? That’s the question.

12. The fundamental issue, then, is tech for normies. By which I mean: Is tech-wise living possible for ordinary people? People who don’t belong to intentional communities? People without college or graduate degrees? People who aren’t married or aren’t in healthy marriages, or who are parents but unmarried? It is possible for working-class families? For families whose parents work double shifts, or households with a single parent who works? For kids who go to daycare or public school? For folks who attend churches that themselves encourage and even require constant active smartphone use? (“Please read along on your Bible app”; “Please register your child at this kiosk, we’ll send a text if we need you to come pick her up.”) From the bottom of my heart, with unfeigned sincerity, I do not believe that it is. And if it is not, what are we left with?

13. This is what I mean when I refer to matching the scale of the problem. Ordinary people live according to antecedent material conditions and social scripts, both of which precede and set the terms for what individuals and families tacitly perceive to characterize “a normal life.” But the material conditions and the social scripts that define our life today are funded, overwritten, and determined by Digital. That is why, for example, the child of friends of mine here in little ol’ Abilene, Texas, was one of exactly two high school freshmen in our local public high school who did not have a smartphone—and why, before fall semester was done, they bought him one. Not because the peer pressure was too intense. Because the pressure from teachers and administrators and coaches was insurmountable. Assignments weren’t being turned in, grades were falling, rehearsals and practices were being missed, all because the educational ecosystem had begun, sometime in the previous decade, to presuppose the presence of a smartphone in the hand, pocket, purse, or backpack of every single student and adult in the school. It is now the center around which all else orbits. The pull, the need, to buy a smartphone proves, in the end, irresistible. It doesn’t matter what you, the individual, or y’all, the household, want. Resistance is futile.

14. Now. Must this lead to despair? Does this imply that resistance to evil is impossible? That there is nothing to be done? That we are at the end of history? No. Those conclusions need not follow necessarily. I don’t think that digital technology as such or in every respect is pure evil. This isn’t the triumph of darkness over light. My children watching Encanto or playing Mario Kart is not the abomination of desolation, nor is my writing these words on a laptop. My point concerns the role and influence and ubiquity of Digital as a power and force in our lives and, more broadly, in our common life. It is that that is diabolical. And it is that that is a wicked problem. Which means it is not a problem that individuals or families have the resources or wherewithal to address on their own—any more than, if the water supply in the state of Texas dried up, this or that person or household could “choose” to resolve the issue on their own. This is why I insisted in my original review that there is something inescapably political, even top-down, about a comprehensive or potentially successful response to Digital’s reign over us. Yes, by all means we should begin trying to rewrite some of the social scripts, so far as our time and ability permit. (I’m less sanguine even here, but I grant that it’s possible in small though important ways.) Nevertheless the material conditions must change for any such minor measures to take hold, not just at wider scale but in the lives of ordinary people. If you’re willing to accept the metaphor of addiction—and I think it’s more than a metaphor in this case—then what we need is for the authorities to turn off the supply, to clamp down on the free flow of the drug we all woke up one day to realize we were hooked on. The thing about a drug is that it feels good. We’re all jonesing for one more hit, click by click, swipe by swipe, like by like. What we need is rehab. But few people check themselves in voluntarily. What most addicts need, most of the time, is what most of us, today, need above all.

An intervention.

Church for normies

In his book Hauerwas: A (Very) Critical Introduction, Nicholas Healy raises an objection with Hauerwas’s ecclesiology. He argues that Hauerwas’s rhetoric and sometimes his arguments present the reader with a church fit only for faithful Christians—that is, for heroes and saints, for super-disciples, for the extraordinarily obedient, the successful, the satisfactory. By contrast, Healy argues that the church ought to be a home and a haven for “unsatisfactory Christians,” and that our doctrine of the church ought to reflect that.

In his book Hauerwas: A (Very) Critical Introduction, Nicholas Healy raises an objection with Hauerwas’s ecclesiology. He argues that Hauerwas’s rhetoric and sometimes his arguments present the reader with a church fit only for faithful Christians—that is, for heroes and saints, for super-disciples, for the extraordinarily obedient, the successful, the satisfactory. By contrast, Healy argues that the church ought to be a home and a haven for “unsatisfactory Christians,” and that our doctrine of the church ought to reflect that.

That phrase, “unsatisfactory Christians,” has stuck with me ever since I first read it. It’s often what I have in mind when I refer to “normie” Christians: ordinary believers most of whose days are filled with the mundane tasks of remaining decent while doing what’s necessary to survive in a hard world: working a boring job, feeding the kids, getting enough sleep, paying the bills, not getting too much into debt, occasionally seeing friends, fixing household or familial problems, maybe taking an annual vacation. Into this all-hands-on-deck eking-out-a-survival life, “being a Christian” is somehow supposed to fit, not only seamlessly but in a transformative way. So you go to church, share in the sacraments, say your prayers, raise your kids in the faith, and generally try to fulfill the duties and roles to which you understand God to have called you.

I used to be Hauerwasian (or Yoderian, before that moniker assumed other connotations) in my ecclesiology, but over the years I’ve come to think of that style of construing Christian discipleship as a well-intended error, though an error all the same. To be clear, I’m not talking about Hauerwas himself—who defends himself against Healy’s critique in a later book—but about the sort of ecclesiology associated with him and with those who have developed his thought over the decades. I’m thinking, that is, of an approach to church that sees it as a small band of deeply committed disciples whose life together is aptly described as an “intentional community.” These are people who know their Bibles, who have strong and well-informed theological opinions, who are readers and thinkers, who have college degrees, who are white collar and/or middle-/upper-middle class, who make common cause to found or form or join a local community defined by a Rule of Life and thick expectations and rich, shared daily practices. Often as not they meet in homes or move into the same neighborhood or even purchase a plot of land for all to live on together.

I would never knock such communities. Extending the monastic vision to include lay people in all walks of life is a lovely development. Though I do worry that such communities are usually short-term arrangements lacking longevity, and that they are typically idealized and overly romantic, nonetheless they represent a healthy response to the vision of the church in the New Testament and sometimes even work out. Nothing but kudos and blessings upon them.

My disagreement is with the view that this vision of church just is what any and every church ought to be, as though all other versions of church must therefore be (1) pale imitations of the real thing, (2) tolerable but incomplete attempts at church, or even simply (3) failed churches. That’s wrong. It’s wrong for many reasons, including exegetical, historical, and theological reasons. But let me give one closer to the ground, rooted in human experience.

The radical church is not a church for normies. To use Healy’s terminology, it’s not a community meant for unsatisfactory Christians. It’s for Christians who have their you-know-what together: Christians who are both able and willing, given their background, education, financial status, temperament, moral and intellectual aptitude, and personal desire, to enter the monastic life, only here as laypersons. It’s certainly possible to make a case, based on the Gospels and the teaching of Christ, that the church exists solely for such Christians, since the condition for faith is discipleship to Christ, and discipleship to Christ is costly. I believe this to be a profound misunderstanding, however, not least because the rest of the New Testament exists. Just read St. Paul. He’ll disabuse you rather quickly of the notion that the church consists of satisfactory Christians. It turns out the church is nothing but unsatisfactory Christians. And if your Christian community is such that no normie would ever dream of visiting or joining it, because it’s clear that he or she is not and would never be up to snuff, then—allow me to suggest—you’re doing it wrong.

The church has to make room for the unsatisfactory, exactly in the manner I described above: the just-getting-by, the I’m-barely-paying-the-bills, the it-took-all-I-had-to-show-up-this-morning, the I’m-doing-my-best, the just-give-me-a-break folks. The holly-ivy Christians, who begrudgingly show up twice a year. The Kichijiros and Simon Peters and doubting Thomases. The addicts who relapse, the gamblers in debt, the porn-addled who can’t quit, the foreclosed-on and laid-off, the perennially fired and out of work, the ex-cons and adulterers and fathers of five kids by three different moms. Is the church not for such as these? “Truly, I say to you, the tax collectors and the harlots go into the kingdom of God before you.”

Our churches may not, must not, fall prey to the temptation that such people have no place in them, because if we believe that, then we will make them such places. Worse, we will inadvertently make them havens for a different kind of person: neither “the least of these” (whom Jesus loves) nor the radical types who flock to intentional communities, but the sort of credentialed professionals who want that sweet, sweet upper-middle-class life alongside others who look and talk and live just like them. Such folks are all unsatisfactory to a person—that’s just to say they’re human—but they present the opposite on the outside. Either way, the undisguised unsatisfactory have nowhere to lay their heads: the well-to-do don’t want them and the radicals can’t receive them.

Does this mean our churches should expect less of their members? Does it mean our churches should restructure their common life? Does it mean churches should function to permit and even welcome the straggler, the good-for-nothing, the failed disciple, the I’m-just-here-to-take-the-Eucharist-and-run type?

Yes. That is exactly what I’m saying. Radicals hate the medieval distinction between the evangelical counsels of perfection and the “lower” universal teachings of Jesus meant for all Christians. But the distinction arose for a reason, and it’s an essential one. Further, it’s why the church, especially in patristic and medieval periods, developed such a strong account of the sacraments as the heart of lay Christian life. The sacraments are pure reception, pure gift: grace upon grace. That’s what a sacrament is, the material sign and instrument of God’s grace, and it’s what the Blessed Sacrament of Christ’s Body and Blood enacts and encapsulates. God willing, the Spirit so moves in the regular, daily and weekly, reception of Holy Communion that a believer is drawn into a lifelong journey of sanctification, what is unsatisfactory (this plain and unimpressive water) being transformed into that which pleases the Lord and edifies his body (the miraculous wine saved best for last). But that’s up to God, and it begins, it does not end, with initiation into and partaking of the liturgical and sacramental life of God’s people.

We need churches that offer and embody and invite people to that, making clear all the while that the summons is for all—especially normies.

Tech-wise BenOp

My friend Jeff Bilbro has raised a question about my review essay in The New Atlantis of Andy Crouch’s new book, The Life We’re Looking For: Reclaiming Relationship in a Technological World. He sees a real tension between the critical questions I pose for Crouch at the end of the review and my essay last year for The Point, in which I defend Wendell Berry against the charge of quietism or apolitical inaction (lodged, in this case, by critic George Scialabba).

My friend Jeff Bilbro has raised a question about my review essay in The New Atlantis of Andy Crouch’s new book, The Life We’re Looking For: Reclaiming Relationship in a Technological World. He sees a real tension between the critical questions I pose for Crouch at the end of the review and my essay last year for The Point, in which I defend Wendell Berry against the charge of quietism or apolitical inaction (lodged, in this case, by critic George Scialabba). If, that is, I argue that Berry is right to insist that living well is worth it even when losing is likely—in other words, when the causes in which one believes and for which one advocates are unlikely to win the day—am I not being inconsistent in criticizing Crouch’s proposal for failing to match the scale of the problem facing us in digital technology? Am I not taking up the role of Scialabba and saying, in so many words, “Lovely prose; bad advice”?

I don’t believe I am, but the question is a sharp one, and I’m on the hook for it. Let me see if I can explain myself.

First, note well that my review is overwhelmingly positive and that I say repeatedly in the closing sections of the essay that Crouch’s proposal is a sensible one; that it may, in fact, be the best on offer; and that it is worth attempting to implement whether or not there is a more scalable alternative to be preferred.

Second, my initial criticism concerns audience. In effect I am asking: Who can put this vision into practice? Who is capable of doing it? Whom is it for? With respect to Berry/Scialabba, that question is immaterial. Scialabba isn’t frustrated or confused by Berry’s intended audience; he actively does not want Berry to be successful in persuading others to adopt his views, because doing so would drain the resources necessary for mass political activism to be effective. Put differently, the Berryan vision is possible, though strenuous. Whereas it isn’t clear to me that Crouch’s vision is possible at all—or at least the question of for whom it may be possible is unclear to me.

Third, then, I want to up the ante on the Crouchian project by comparing its scale to the scale of the problem facing us, on one hand, and by asking after its purpose, on the other. It seems to me that The Life We’re Looking For does believe, or presuppose, that the Tech-Wise BenOp (or, if we want to uncouple Crouch from Dreher, the Pauline Option) has the power to effect, or is ordered to, the transformation of our common life, our culture, etc. Granted that such transformation may take decades or centuries, transformation is clearly in view. But this, too, is distinct from Berry’s stance. Berry does not believe his vision of the good life is a recipe for transformation. He does believe that large-scale transformation is impossible apart from local and even personal transformation. That, however, is a different matter than proposing a means for change. In sum, Berry believes that (1) the good life is worth living whatever the future may hold, (2) the good life is not a plan for change, and (3) the possibility of change requires the integration of national and local, cultural and personal, theoretical and practical. I affirm all this. But these points are distinct from (though not opposed to) Crouch’s proposal.

Returning to scale helps to clarify the difference. I admit in the review that it may genuinely be impossible to match the scale of the problem of digital technology without grave injustice. Nonetheless I hold that, given that scale, I cannot see how Crouch’s Pauline Option is a live possibility for any but saints. And as I say there, salvation from the tyranny of tech “must be for normies, not heroes.”

Let me make this more personal. Across my entire life I have not known a single household or family that fits the vision of being “tech wise” as laid out in either this book or Crouch’s previous book. Whether the folks in question were single, married, or parents, whether they were Christians or not, whether they were affluent or not, whether they were Texan or not, whether they were suburban or not, whether they were educated or not—the inside of the home and the habits of the household were all more or less the same, granting minor differences. Everyone has multiple TVs. Everyone has laptops and tablets. Everyone has video games. Everyone has smart phones. Everyone subscribes to streaming services. Everyone watches sports. Everyone is on social media. Everyone, everyone, everyone. No exceptions. The only differences concern which poison one prefers and how much time one gives to it.

I’m not throwing stones. This description includes me. I assume it includes you, too. The hegemony of the screen is ubiquitous, an octopus whose tentacles encircle and invade every one of our homes. No one, not one is excluded.

Some folks are more intentional than others; some of them even succeed in certain practices of moderation. But does it really make a difference? Is it really anything to write home about? Does it mark these homes off from their neighbors? Not at all. I repeat: Not once have I entered a single home that even somewhat resembles the (already non-extreme!) vision of tech-wisdom on offer in the pages of Crouch’s books.

This is what I mean by scale. It’s like we’re all on the bottom of the ocean, but some of us are a few yards above the rest. Are such persons technically closer to the surface? Sure. Are they still going to drown like the rest of us? Absolutely.

*

I hope all this makes clear that I’m not contesting the wisdom or goodness or beauty of Crouch’s vision of households nurturing a technological revolution in nuce. I want to join such a resistance movement. But does it exist? More to the point, is it possible?

What I’ve come to believe is that, more or less full stop, it is not possible—so long, that is, as our households remain occupied territory. The flag of Silicon Valley waves publicly and proudly in all of our homes. I see it everywhere I go. It’s like the face of Big Brother. It just keeps on flapping and waving, waving and smiling, world without end, amen.

Perhaps “scale” is a misleading term. More than scale the challenge is how deep the roots of the problem lie. Truly to get a handle on it, truly to begin the revolution, an EMP would have to be detonated in my neighborhood. We’d have to throw our screens in a great glorious bonfire, turn off our wi-fi, and rid our homes of every “smart” device (falsely so called) and every member in that dubious, diabolical category: “the internet of things.” We’d have to delete Twitter, Instagram, Facebook, Snapchat, and TikTok from our phones. We’d have to cancel our subscriptions to Netflix, Disney, Apple, HBO, Hulu, and Amazon. We’d have to say goodbye to it all, and start over.

I don’t mean we have to live in a post-digital world to live sane lives. (Though some days I do wonder whether that may be true: viva la Butlerian Jihad!) I mean our lives are already so integrated with digital as to qualify as transhuman. We must face that fact squarely: If we are already cyborgs in practice, then disconnecting a few of the tubes while remaining otherwise hooked up to the Collective isn’t going to cut it.

Nor—and this is a buried lede—is any of this possible, if it is possible, for any but the hyper-educated or hyper-affluent. Most people, as I comment in the review, are just trying to survive:

We are too beholden to the economic and digital realities of modern life — too dependent on credit, too anxious about paying the rent, too distracted by Twitter, too reliant on Amazon, too deadened by Pornhub — to be in a position to opt for an alternative vision, much less to realize that one exists. We’ve got ends to meet. And at the end of the day, binging Netflix numbs the stress with far fewer consequences than opioids.

Yet all the hyper-educated and hyper-affluent people I now are just as plugged-in as those with fewer degrees and less money. Put most starkly, I read Crouch’s book as if it were a sermon preached by an ex-Borg to the Borg Hive. But individual Borg aren’t capable of disconnecting themselves. That’s what makes them the Borg.

As they say, resistance is futile.

*

My metaphors and rhetoric are outstripping themselves here, so let me pull it back a bit, not least because the point of this post isn’t to criticize Crouch’s book but to show that my (modestly!) critical questions aren’t at odds with my defense of Berry.

Let me summarize my main points, before I add one final word about scale, that word I keep using but not quite defining or addressing.

Crouch’s book is an excellent and beautiful vision of what it means to be human, at all times and especially today, in a world beset by digital technology.

I don’t know whether Crouch envisions that vision to be achievable by just anyone at all; and, if not, then by whom in particular.

I don’t know whether Crouch’s vision is possible in principle, at least for normal people with normal jobs and normal lives.

Even if it were possible in principle for the few saints and heroes among us, I don’t know whether it would make a difference except to themselves.

This last observation is not a criticism in itself, but it becomes a criticism if Crouch believes that cultural transformation occurs from the ground up through the patient faithfulness of a tiny minority of persons leavening society by their witness, eventuating in radical social transformation.

Points two through five are not in tension with my defense of Berry against Scialabba, because (a) Berry’s vision is livable, (b) it is livable by normies, (c) it is not designed or proposed in order to effectuate mass change, and (d) he knows this and believes it is worth doing anyway.

Clearly, I have set myself up here to be disproved: If Crouch’s vision is not only possible to be lived in general but is being lived right now, as we speak, by normies, then he’s off the hook and I’ve got pie on my face. More, if he doesn’t believe that—or is not invested in the likelihood that—this vision, put into practice by normal folks, will or should lead to social, cultural, economic, and political transformation, then that’s a second pie on top of the first, and I hereby pledge to repent in digital dust and ashes.

Nothing would make me happier than being shown to be wrong here. I want Crouch to be right, because I want nothing more than for my life and the lives of my friends and neighbors (and, above all, those of my children) to be free of the derelictions and defacements of digital. Not only that, but there’s no one I trust more on this issue than Crouch. I assign The Tech-Wise Family to my students every year, and practices he commends there have made their way into my home. I owe him many debts.

But I just can’t shake the feeling that the problem is even bigger, even nastier, even deeper and more threatening than he or any of us can find it within us to admit. That’s what I mean when I refer to “scale.” Permit me to advert to one last overwrought analogy. Berry wants us (among other things) to live within limits, on a plot of land that we work by our own hands to bring forth some allotment of food for us, our household, our neighbors, our animals. He doesn’t ask us to breathe unpolluted oxygen, to live on a planet without air pollution. That’s now, regrettably, a fact of life; it encompasses us all. By contrast, reading The Life We’re Looking For I get one of two feelings: either that unpolluted oxygen is available, you just have to know where to find it; or that the pollution isn’t so bad after all. Maybe there really are folks who’ve fashioned or found oxygen masks here and there around the globe. Maybe I’ve just been unfortunate not to have spotted any. But I fear there are none, or there aren’t nearly enough to go around.

In brief, the Hive isn’t somewhere else or other than us; we are the Hive, and the Hive is us. It’s just this once-blue planet spinning in space, now overtaken by the tunnels and tubes, the darkness and silence of the Cube. If there’s a way out of this digital labyrinth, I’m all ears. All day long I’m looking for that crimson thread, showing the way out. If someone—Bilbro, Berry, Crouch, whoever—can lead the way, I’ll follow. The worry that keeps me up nights, though, is that there is no exit, and we’re deceiving ourselves imagining there is.

Creatura verbi divini

On the Mere Fi podcast earlier this week, both Derek and Alastair pressed me on the question of whether the church is “the creature of God’s Word.” The theological worry here is that if one affirms, with catholic tradition, that the church creates the canon, then the proper order between the two has been inverted, since the people of God is the creatura verbi divini, not the other way around. How, after all, could it be otherwise?

On the Mere Fi podcast earlier this week, both Derek and Alastair pressed me on the question of whether the church is “the creature of God’s Word.” The theological worry here is that if one affirms, with catholic tradition, that the church creates the canon, then the proper order between the two has been inverted, since the people of God is the creatura verbi divini, not the other way around. How, after all, could it be otherwise?

You can listen to my answer on the pod. My reply was simple, though I can’t speak to how well I articulated it there. Here, at least, is what I would say in expanded form.

The word of God creates the church; but the church creates the canon. This is not a contradiction because, even though Holy Scripture mediates and thus is the word of the living God to his people, the canon of texts that Scripture comprises is wholly (though not only) human, historical, and just so a product of the church. Moreover, the canon as such does not exist at the church’s founding, traditionally identified with Pentecost. No apostolic writing is extant at that moment. Apostolic writings begin to be written a decade or two following; they are not completed for at least a half century hence (maybe more); and the canon or formal collection or list of apostolic writings received as authoritative divine Scripture on the part of the church does not exist in any official way for some centuries. And even once the canon is explicit, unanimity and universality of its acceptance take even more centuries to arrive. (If one agrees with the Protestant reformers regarding the excision from the canon of such deuterocanonical books as the Wisdom of Solomon and Tobit, then in point of fact the canon takes a full fifteen centuries to come into its final, public form.)

In my view, magisterial Protestant doctrines of Scripture elide this crucial distinction in their claim that the church is created by the word of God and, thus, that Scripture creates the church. The word of God does indeed found the church, both (1) in the primary sense that the risen incarnate Logos from heaven pours out the Spirit of the Father on his apostles and (2) in the secondary sense that the apostles’ proclamation of the word of the gospel convicts and converts sinners to Christ wherever they travel, bearing witness to the good news. This is the running theme of the book of Acts. Nevertheless it remains the case that, within the very narrative of Acts, no canon of Scripture exists. Recall that St. Luke does not record the writing of any canonical text! Those texts he does record, such as the letter of St. James and the Jerusalem council to gentile believers, are not found elsewhere in the canon, but only here, as reported speech.

In our conversation, Alastair pressed a different point, an important one with which I agree but which, I think, I understand differently than he does. He observed that what doctrines of Scripture often overlook is the manifold and altogether material ways in which the production and dissemination of graphai influenced and shaped the early messianic assemblies dotting the shoreline of the Mediterranean basin. Apart from and prior to any theological redescription, that is, we can see just how letter-centric and letter-formed the early Christian communities were, evident in the extraordinary literary production of St. Paul alone. Letters (and homilies, and histories, and apocalypses, and …) are written, copied, distributed, shared, read aloud in worship, studied by the saints, transmitted and republished, so on and so forth, and this diverse and fascinating process is up and running, at the absolute latest, by the end of the second decade of the church’s existence.

As I say, I agree wholeheartedly with this observation. And it certainly bears on our theological and not only our historical understanding of the church’s origins. But, so far as I can tell, it doesn’t bear on the specific point raised by the question of whether the canon creates the church or vice versa.

That is to say: Granting the existence and influence of Pauline and other literatures in the first century of the church’s life (and on, indefinitely, into the future), this phenomenon seems to me to confirm rather than to contradict or even to complicate my original answer offered above. Yes, God’s word founds the church, both from heaven and through the spoken and, later, written words of the apostles. But from this undeniable fact we may not draw the conclusion that the canon—or even the apostolic writings eventually canonized—“create” the church, and for the same reasons. The canon does not exist in the time of the apostles. And although, intermittently and somewhat haphazardly, written apostolic documents begin circulating in the second half of the first century AD, these are far from universally shared by ekklesiai around the known world. There are churches in Africa and India and Spain and elsewhere that simply lack all or most of the apostolic writings later canonized until the second and even sometimes into the third or fourth centuries. The church simply cannot be said to be a creature of the canon or even of the apostolic texts subsequently included in the canon. The church predates both by decades, even centuries. Certain churches do receive and benefit from certain texts authored or commissioned by apostles. But for some time they are in the minority, and even they (i.e., the churches in question) preexisted their reception of any apostolic text whatsoever. Not that they preexisted apostolic teaching—but then, this question concerns graphai, not oral doctrina.

I hope this clarification is responsive to both Derek’s and Alastair’s questions and concerns. I hope especially that it is cogent. I look forward to hearing from them or others regarding where I might be wrong.

I’m on Mere Fidelity

Did I say quit podcasts? I meant all of them except one.

Did I say quit podcasts? I meant all of them except one.

I’m on the latest episode of Mere Fidelity, talking about my book The Doctrine of Scripture and, well, the doctrine of Scripture. (Links: Google, Spotify, Apple, Soundcloud.) It was a pleasure to chat with Derek and Alastair and (surprise!) Timothy. Matt had to bail last minute. I can only assume he was nervous.

No joke, it was an honor to be on. For the last decade, I have lived by the mantra, “No podcasts before tenure.” I’ve turned down every invitation. In 2020–21 I participated in three podcasts as a member of The Liberating Arts, the first two as the interviewer (of Alan Noble and Jon Baskin, respectively) and the third as interviewee, speaking on behalf of the project (this was 11 months ago, but the podcast just posted this week, as it happens). In other words, this experience with Mere Fi was for all intents and purposes my first true podcast experience, in full and on the receiving end.

It was fun! I hope I didn’t flub too many answers. I tend to speak in winding paragraphs, not in discrete and manageable sentences. Besides, it’s hard to compete with Alastair’s erudition—and that accent!

Check it out. And the Patreon, where there’s a +1 segment. Thanks again to the Mere Fi crew. I give all of you dear readers a big glorious exception to go and listen to them. They’ve got the best theology pod around. What a gift to be included on the fun.

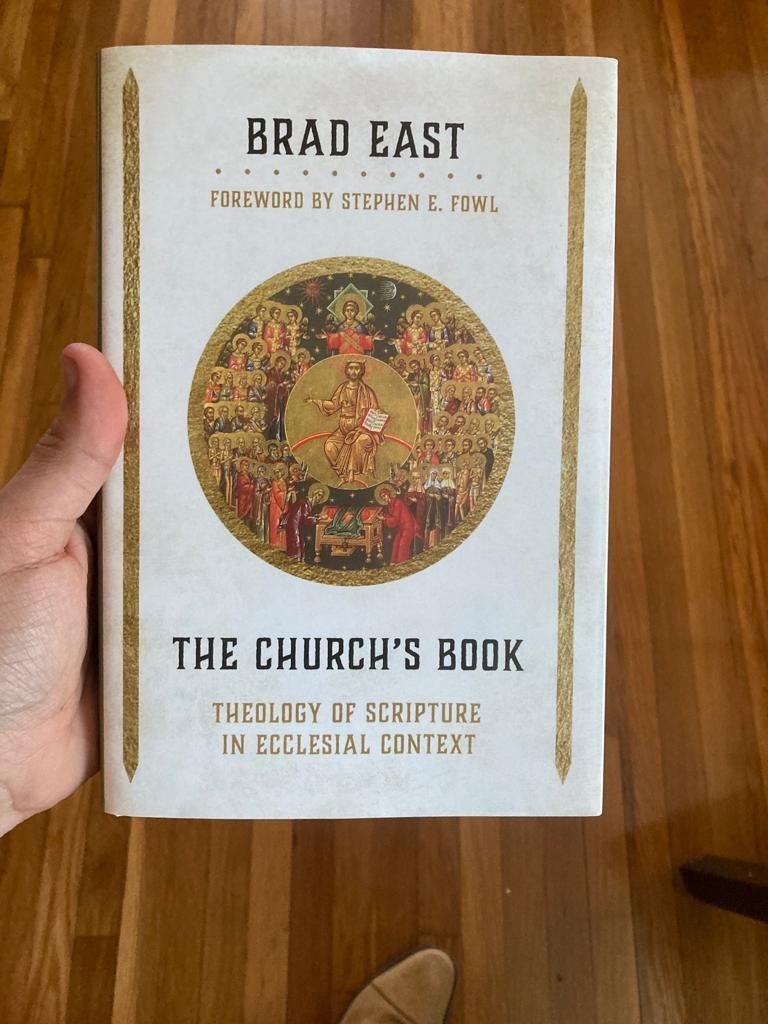

The Church’s Book is here!

My new book, The Church’s Book, is here! Order today.

It’s here!

Or if you want a snazzy wrap-around image of the whole front and back matter…

The book is ready for order anywhere books are sold: Amazon, Bookshop, Eerdmans, elsewhere. Some websites may say that the publication date is May 24, but it’s available to be shipped at this moment—folks I know who pre-ordered it have already received a copy or are getting theirs by mail in a matter of days. And the Kindle edition will be available Tuesday next week, the 26th.

Here’s the book description:

What role do varied understandings of the church play in the doctrine and interpretation of Scripture?

In The Church’s Book, Brad East explores recent accounts of the Bible and its exegesis in modern theology and traces the differences made by divergent, and sometimes opposed, theological accounts of the church. Surveying first the work of Karl Barth, then that of John Webster, Robert Jenson, and John Howard Yoder (following an excursus on interpreting Yoder’s work in light of his abuse), East delineates the distinct understandings of Scripture embedded in the different traditions that these notable scholars represent. In doing so, he offers new insight into the current impasse between Christians in their understandings of Scripture—one determined far less by hermeneutical approaches than by ecclesiological disagreements.

East’s study is especially significant amid the current prominence of the theological interpretation of Scripture, which broadly assumes that the Bible ought to be read in a way that foregrounds confessional convictions and interests. As East discusses in the introduction to his book, that approach to Scripture cannot be separated from questions of ecclesiology—in other words, how we interpret the Bible theologically is dependent upon the context in which we interpret it.

Here are the blurbs:

“How we understand the church determines how we understand Scripture. Brad East grounds this basic claim in a detailed examination of three key heirs of Barthian theology—Robert Jenson, John Webster, and John Howard Yoder. The corresponding threefold typology that results —church as deputy (catholic), church as beneficiary (reformed), and church as vanguard (believers’ church)—offers much more than a description of the ecclesial divides that undergird different views of Scripture. East also presents a sustained and well-argued defense of the catholic position: church precedes canon. At the same time, East’s respectful treatment of each of his theological discussion partners gives the reader a wealth of insight into the various positions. Future discussions about church and canon will turn to The Church’s Book for years to come.”

— Hans Boersma, Nashotah House Theological Seminary“Theologically informed, church-oriented ways of reading Scripture are given wonderfully sustained attention in Brad East’s new book. Focusing on Karl Barth and subsequent theologians influenced by him, East uncovers how differences in the theology of Scripture reflect differences in the understanding of church. Ecclesiology, East shows, has a major unacknowledged influence on remaining controversies among theologians interested in revitalizing theological approaches to Scripture. With this analysis in hand, East pushes the conversation forward, beyond current impasses and in directions that remedy deficiencies in the work of each of the theologians he discusses.”

— Kathryn Tanner, Yale Divinity School“In this clear and lively volume, Brad East provides acute close readings of three theologians—John Webster, Robert W. Jenson, and John Howard Yoder—who have all tied biblical interpretation to a doctrine of the church. Building on their work, he proposes his own take on how the church constitutes the social location of biblical interpretation. In both his analytical work and his constructive case, East makes a major contribution to theological reading of Scripture.”

— Darren Sarisky, Australian Catholic University“If previous generations of students and practitioners of a Protestant Christian doctrine of Holy Scripture looked to books by David Kelsey, Nicholas Wolterstorff, and Kevin Vanhoozer as touchstones, future ones will look back on this book by Brad East as another. But there is no ecclesially partisan polemic here. This book displays an ecumenical vision of Scripture—one acutely incisive in its criticism, minutely attentive in its exposition, and truly catholic and visionary in its constructive proposals. It has the potential to advance theological discussion among dogmaticians, historians of dogma, and guild biblical exegetes alike. It is a deeply insightful treatment of its theme that will shape scholarly—and, more insistently and inspiringly, ecclesial—discussion for many years to come.”

— Wesley Hill, Western Theological Seminary“In the past I’ve argued that determining the right relationship between God, Scripture, and hermeneutics comprises the right preliminary question for systematic theology: its ‘first theology.’ Brad East’s The Church’s Book has convinced me that ecclesiology too belongs in first theology. In weaving his cord of three strands (insights gleaned from a probing analysis of John Webster, Robert Jenson, and John Howard Yoder), East offers not a way out but a nevertheless welcome clarification of where the conflict of biblical interpretations really lies: divergent understandings of the church. This is an important interruption of and contribution to a longstanding conversation about theological prolegomena.”

— Kevin J. Vanhoozer, Trinity Evangelical Divinity School“For some theologians, it is Scripture that must guide any theological description of the church. For others, the church’s doctrines are normative for interpreting Scripture. Consequently, theologians have long tended to talk past one another. With unusual brilliance, clarity, and depth, Brad East has resolved this aporia by arguing that the locus of authority lay originally within the people of God, and thus prior to the development of both doctrine and Scripture. And so it is we, the people of God, who are prior, and who undergird both, and thereby offer the possibility of rapprochement on that basis. East’s proposal is convincing, fresh, and original: a genuinely new treatment that clarifies the real issues and may well prepare for more substantive ecumenical progress, as well as more substantive theologies. This is a necessary book—vital reading for any theologian.”

— Nicholas M. Healy, St. John’s University“All of the discussions in this book display East’s analytical rigor and theological sophistication. As one of the subjects under discussion in this book, I will speak for all of us and say that there are many times East is able to do more for and with our work than we did ourselves. . . . I look forward to seeing how future theological interpreters take these advances and work with them to push theological interpretation in new and promising directions.”

— Stephen E. Fowl, from the foreword

This book has been more than a decade in the making, being a major revision of my doctoral dissertation at Yale. It’s a pleasure and a relief to hold it in my hands. I’m so eager to see what others make of it. I’m especially grateful for it to be coming out so soon after the release last fall of The Doctrine of Scripture, my first book. The two are complementary volumes: one provides scholarly, theoretical, genealogical, and ecclesiological scaffolding; the other builds a constructive proposal on that basis. The sequence of their release reverses the order in which they were written, but that’s neither here nor there. Together, they comprise about 250,000 words on Christian theology of Holy Scripture and its interpretation. Add in my journal articles and you’ve got 300K words. That’s a lot, y’all. I hope a few folks find something worthwhile in them. Always in service to the church and, ultimately, to the glory of God.

What a joy it is to do this job. Very thankful this evening. Blessings.

Inoculation

Over the last year I’ve noticed something of a theme emerging on this blog. The theme is what people, especially Christians, and most of all well-educated Christians, feel permitted or pressured to believe (or not). I think a good deal of my experience of this phenomenon is a function of having lived for eight years outside of Texas or even the Bible belt—three years in Atlanta (technically the South but not exactly a small rural town in Louisiana) then five years in New Haven, Connecticut.

Over the last year I’ve noticed something of a theme emerging on this blog. The theme is what people, especially Christians, and most of all well-educated Christians, feel permitted or pressured to believe (or not). I think a good deal of my experience of this phenomenon is a function of having lived for eight years outside of Texas or even the Bible belt—three years in Atlanta (technically the South but not exactly a small rural town in Louisiana) then five years in New Haven, Connecticut. At least weekly and sometimes daily a friend, a colleague, a pastor, or a student will remark in my presence about some topic, and invariably the remark reveals that s/he understands it to be outdated, unenlightened, or outlandish. As I wrote yesterday, usually the topic is one I care about and, indeed, the belief presumed to call for nothing so much as an eye-roll is one I myself hold.

I wrote last year about the existence of angels as a case study. At the very moment that certain aspirationally progressive (in west Texas “progressive” means “moderate-to-slightly-left-of-center on certain issues”) seminarians and pastors unburden themselves of belief in superstitious follies like angels—having belatedly received the decades-old message from third-rate demythologizers that celestial beings belong to a mythological age—at this moment, as I say, angels and demons are sexy again in academic scholarship. I could walk through the hallways of the most liberal seminaries in the country holding a sign that read “I believe in angels!” and from most professors it would elicit no more than a shrug. One more reminder that being intellectually in vogue is a moving target; best not to make the attempt in the first place.

But that’s not my point at present. I’ve already written about all that. Here’s my point.

I understand why people feel pressure to believe, or to cease to believe, in this or that old-fashioned thing. Likewise I understand why they assume that I—returning from a half-decade sojourn among the coastal elites, having pitched my tent in the Acela corridor, now with an Ivy doctorate in hand—not only share their up-to-date beliefs but will do them a solid by confirming them in their up-to-date-ness. I get it.

But the secret about having gotten my PhD at Yale isn’t that I learned the cutting edge and now live my life teetering on it. The opposite is the case. I didn’t journey to the Ivy League only to be disabused of all those silly beliefs I came in the door with—about God, Christ, Scripture, resurrection, and the rest. What I received was far better, if wholly unexpected.

What I received was inoculation.

What do I mean? I mean that I learned the invaluable intellectual lesson that knowledge, intelligence, and education are not a function of fads. I learned that substituting social trends for reasoned conviction is foolish. I learned that no one else can do your thinking for you. I learned that coordinating one’s own beliefs to the beliefs of an ever-changing and amorphous elite is a fool’s errand and a recipe for spiritual aimlessness. I learned that smart people are often wicked, and that sometimes even smart people are stupid—in the sense that raw intelligence is no match for wisdom, prudence, and practical reason.

Most of all, I learned that there are no “outdated” beliefs in Christian theology. As Hauerwas might put it, passé is not a theological category. Think of any doctrine or conviction that is particularly unhip today, or rarely spoken of, or even that you might be embarrassed to admit you believe in mixed company. At Yale, and in the circles of folks who criss-cross Ivy campuses and circuits and conferences, I met people who believed in every single one of those unfashionable doctrines, and they were the smartest, most well-read people I’ve ever met in my life. Certainly smarter and better read than I’ll ever be. To be clear, that fact alone doesn’t make them right: their frumpy beliefs may be erroneous. But the lesson isn’t that prestige or scholarly caliber validate theological ideas. The lesson, rather, is that the notion of some threshold of intelligence or erudition beyond which certain beliefs simply cannot across is a lie. Such a threshold does not exist.

In short, if what you want is for folks with an IQ above X or a PhD from Y to tell you what you’re allowed to believe while remaining a reasonable person, I’ve got some good news and some bad news. The bad news is that you can be a reasonable person and believe just about anything. No one above your rank is going to set the terms for what you’re permitted to suppose to be true about God, the world, and everything else. The good news is just a reiteration of these same truths, only in a different register: No one gets to make you feel bad for believing what you do. That’s not a license to believe untrue or foolish or evil things. It’s a liberation from feeling like personal conviction is a matter of not being made fun of by the Great and the Good peering over your shoulder, looking down their noses at you. Truth is not a popularity contest. Right belief does not follow from peer pressure. Be free. Be inoculated, as I was. Ever since leaving I’ve found myself blessedly rid of that low gnawing anxiety that someone is going to find me out, and what they’re going to find is that I’m a deplorable—not because what I believe is actually risible or indefensible, but because for about fifteen seconds of cultural time something I’d be willing to stake my life on (as I have, however falteringly) has become intellectually unstylish.

Style is deceptive, and the approval of the world is fleeting; but the one who fears the Lord will be praised. Fear God, not unpopularity. Your life as a whole will be happier, for one, but more than anything your intellectual life will benefit. Seek the truth for its own sake, and the rest will take care of itself.

The uses of conservatism

In the Wall Street Journal a couple weeks back Barton Swaim wrote a thoughtful review of two new books on political conservatism, one by Yoram Hazony and one by Matthew Continetti. The first is an argument for recovering what conservatism ought to be; the second, a history of what American conservatism has in fact been across the last century.

In the Wall Street Journal a couple weeks back Barton Swaim wrote a thoughtful review of two new books on political conservatism, one by Yoram Hazony and one by Matthew Continetti. The first is an argument for recovering what conservatism ought to be; the second, a history of what American conservatism has in fact been across the last century.

Swaim is appreciative of Hazony’s manifesto but is far more sympathetic to Continetti’s more pragmatic approach. Here are the two money paragraphs:

The essential thing to understand about American conservatism is that it is a minority persuasion, and always has been. Hence the term “the conservative movement”; nobody talks of a “liberal movement” in American politics, for the excellent reason that liberals dominated the universities, the media and the entertainment industry long before Bill Buckley thought to start a magazine. Mr. Continetti captures beautifully the ad hoc, rearguard nature of American conservatism. Not until the end of the book does he make explicit what becomes clearer as the narrative moves forward: “Over the course of the past century, conservatism has risen up to defend the essential moderation of the American political system against liberal excess. Conservatism has been there to save liberalism from weakness, woolly-headedness, and radicalism.”

American conservatism exists, if I could put it in my own words, to clean up the messes created by the country’s dominant class of liberal elites. The Reagan Revolution wasn’t a proper “revolution” at all but a series of conservative repairs, chief among them reforming a crippling tax code and revivifying the American economy. The great triumph of neoconservatism in the 1970s and ’80s was not the formulation of some original philosophy but the demonstration that liberal policies had ruined our cities. Richard Nixon won the presidency in 1968 and again in 1972 not by vowing to remake the world but by vowing to clean up the havoc created by Lyndon Johnson when he tried to remake Southeast Asia. George W. Bush would draw on a form of liberal idealism when he incorporated the democracy agenda into an otherwise defensible foreign policy—a rare instance of conservatives experimenting with big ideas, and look where it got them.

The three sentences in bold are, I think, the heart of Swaim’s point. Here’s my comment on his claim there.

At the descriptive level, I don’t doubt that it’s correct, if incomplete. At the normative level, however, it seems to me to prove, rather than confound, Hazony’s argument. For Hazony represents the conservative post-liberal critique of American conservatism, and that critique is this: American conservatism is a losing bet. It has no positive governing philosophy. It knows only what it stands against. Which is to say, the only word in its political vocabulary is “STOP!” (Along with, to be sure, Trilling’s “irritable mental gestures.”) Yet the truth is that it never stops anything. It merely delays the inevitable. In which case, American conservatism is good for nothing. For if progressives have a vision for what makes society good and that vision is irresistible, then it doesn’t matter whether that vision becomes reality today versus tomorrow. If all the conservative movement can do is make “tomorrow” more likely than “today,” might as well quit all the organizing and activism. Minor deferral isn’t much to write home about if you’re always going to lose eventually.

Besides, in the name of what exactly should such delay tactics be deployed? Surely there must be a positive vision grounding and informing such energetic protest? And if so, shouldn’t that be the philosophy—positive, not only negative; constructive, not only critical; explicit, not only implicit—the conservative movement rallies around, articulates, celebrates, and commends to the electorate?

Swaim is a prolific and insightful writer on these issues; not only does he have an answer to these questions, I’m sure he’s on the record somewhere. Nevertheless in this review there’s an odd mismatch between critique (of Hazony) and affirmation (of Continetti). If all the American conservative movement has got to offer is the pragmatism of the latter, then the philosophical reshuffling of the former is warranted—at least as a promissory note, in service of an ongoing intellectual project. That project is an imperfect and an unfinished one, but it’s far more interesting than the alternative. Whether we’re talking politics or ideas, we should always prefer the living to the walking dead.

“As we all know”

I have a friend who once told me of a professor he had in seminary. She instructed the class at the outset of the semester that, when they wrote their papers, she wanted them to imagine her peering over their shoulder. At every sentence featuring a claim, an assertion, or an assumption, they should imagine her asking them, “How do you know that?”

I have a friend who once told me of a professor he had in seminary. She instructed the class at the outset of the semester that, when they wrote their papers, she wanted them to imagine her peering over their shoulder. At every sentence featuring a claim, an assertion, or an assumption, they should imagine her asking them, “How do you know that?”

This bit of imaginative pedagogy might be a recipe for paper-writing anxiety, but it’s a good bit of writing advice. It’s a strong but necessary dose of epistemic humility. So little of what we take for granted is actually something we know, or at least can claim to know with some confidence, much less provide cogent reasons for knowing it. That’s not a problem in daily life most of the time. It’s rightly a matter for conscious attention in the academy, though.

I think of this anecdote regularly, for the following reason. In my experience, people consistently take for granted that they know in advance what I believe, including about the most important or controverted of matters. I don’t mean, say, that non-Christians assume I believe in God. That would be a reasonable assumption to make, given who I am and what I do. I mean fellow Christians who, because of my education or my profession or my reading habits or some other set of factors, project onto me beliefs regarding topics about which they have never heard me speak and about which I have never written.

It’s become a recurring phenomenon. Before commenting on a subject, a friend or acquaintance or colleague or person I’ve just met will either say aloud or imply, “As we all know…” or “As I’m sure you, like me, believe…” or “As any reasonable person would suppose…” or “Obviously…” or “We, unlike they, think…” or some similar formulation. I’ve come to learn that the phrase, spoken or unspoken, is a social cue. The other person is marking off the fearsome or foolish They from the wise or educated Us. Whatever the issue—usually moral, political, or theological—there is one self-evident Right Answer for People Like Us; but People Unlike Us (the dummies, the fundies, the voters or church folk who can’t be trusted) think otherwise, for some inexplicable reason. Typically the implication is that They are bad people; or, even more condescendingly, They would surely agree with Us if only They had (Our) education. Bless Their hearts, if only They knew better!

What’s remarkable is that, nine times out of town, the belief my interlocutor is attributing to Them is in fact my own. If I were inclined to take offense, I could do so with justice. I’m not so inclined, however, for the simple reason that I’m secure in my own convictions. I don’t need to roll my eyes at those I disagree with in order to feel confident in what I believe to be true. Nor do I need to whisper about Them in mock-conspiratorial or patronizing tones. After all, one thing all my education has done for me is show me how far from obvious any answer to any question is, certainly those questions that animate and roil our common life. People who think I’m wrong aren’t stupid; nor are they ignorant. They’ve merely come to a different judgment about a complex question than the one I have. Logically, I think they’re wrong just as they think I’m wrong; one of us is right (unless both of us are wrong and someone else is right), and this calls for humility, because it’s difficult to say in the moment, from the midst of one’s all-too-parochial life, whether one’s reasons for one’s beliefs are strong, weak, or just post hoc justifications for what one wishes were true or was raised to believe.

In any case, what most fascinates me here is the social phenomenon of presumptive projection onto others of what they must believe, given their intelligence, education, career, or what have you. I’m struck by the sheer lack of curiosity on display. People rarely ask me, directly, what I think about X or Y. Not that they don’t want to talk about it (whatever it is). Usually, though, they dance around the issue; or they assume they know what I think, and take the trouble to inform me of it. I sometimes wonder what would happen if I began, however so gently, to commit the faux pas of pausing the conversation in order to clarify, in no uncertain terms, that the Bad Belief my interlocutor has so passionately forced onto a Benighted They is actually my own. I almost always avoid doing so, since it would likely embarrass the other person, make him feel defensive, ruin the chat we were having , etc. On the other hand, it might actually make for a deeper and richer encounter, not least because here, in the flesh, would be a member of Team Stupid—ask me anything! A real education might ensue, in which it would become evident (using the same word in a different vein) that the world isn’t divided into stupid and smart groups, the latter tolerating the former with magnanimous mercy. This might also encourage avoiding such presumption in the future, and seeking to learn and to understand what other people believe and why.

Then again, maybe not. Regardless, the experience is a lesson in itself. Don’t assume you know what others think, and don’t carve up your neighbors into Good and Evil. Allow yourself to be surprised. People you love and respect have different beliefs than you. Formal education is not a one-way ticket to enlightenment, where “enlightenment” means “believe the same things as you.” Be curious. Ask away. You might learn a thing or two. You might even find one day that your mind has been changed. Imagine that.

Webinar: God’s Living Word

Earlier this week I was honored to participate in a live webinar hosted by the Siburt Institute for Church Ministry, which is a part of the College of Biblical Studies here at ACU. The webinar was in a series called Intersection; the topic was Scripture, using my book published last year as a point of departure. The conversation was hosted by Carson Reed and Randy Harris and lasted about an hour. It was a pleasure to participate. I’ve embedded the video below, but you can also find it here and here. Enjoy.

Earlier this week I was honored to participate in a live webinar hosted by the Siburt Institute for Church Ministry, which is a part of the College of Biblical Studies here at ACU. The webinar was in a series called Intersection; the topic was Scripture, using my book published last year as a point of departure. The conversation was hosted by Carson Reed and Randy Harris and lasted about an hour. It was a pleasure to participate. I’ve embedded the video below, but you can also find it here and here. Enjoy.

The vanity of theologians

The love of God in Christ is the model of all good theological work. That is Barth's basic thesis: “If the object of theological knowledge is Jesus Christ and, in him, perfect love, then Agape alone can be the dominant and formative prototype and principle of theology.” Yet who among us would claim to consistently meet this standard? It is one thing to agree that teaching ought to be an act of self-emptying love on behalf of students, but quite another to teach that way.

The love of God in Christ is the model of all good theological work. That is Barth's basic thesis: “If the object of theological knowledge is Jesus Christ and, in him, perfect love, then Agape alone can be the dominant and formative prototype and principle of theology.” Yet who among us would claim to consistently meet this standard? It is one thing to agree that teaching ought to be an act of self-emptying love on behalf of students, but quite another to teach that way. And while each of us falls short of this ideal in our own ways, Barth draws our attention to an especially corrosive vice that commonly infects us. The illness presents as, among other things, an excessive concern for our reputations; a morbid craving for praise; a narcissistic pretentiousness combined with insecurity; a relentless desire to outdo our colleagues and to broadcast our accomplishments; a loveless envy when others succeed; and a gloomy anxiety about our legacies, about how people will remember and evaluate us when we're dead. The vice, of course, is vanity, and Barth considers it a menacing threat to theologians.

To put it simply, Barth thinks a vain theologian is an embodied contradiction of the gospel and the very antithesis of Jesus Christ himself. And he doesn't care how obvious this is. Barth doesn't care that making fun of self-important theologians is by now a tired cliché. He knows that vanity disables us, and because of that he is willing to sound the alarm. And we would do well not to evade his critique by dismissing it as moralistic or judgmental or whatever. . . .

It is tempting to interpret passages like these as nothing more than Barth's way of deflecting the ocean of praise that was being directed at him toward the end of his life. He was, after all, the most famous theologian in the world. When he traveled to America to give the first five lectures in Evangelical Theology, Time magazine put him on its cover. Or perhaps one sees in these statements a tacit admission that Barth did not always manage to live up to his own standards, and that is certainly true. But Barth is aiming these passages at us too, and only an instinct for self-protection would lead us to think otherwise. Because if he wasn't troubled by our desire for greatness, he wouldn't aggressively remind us that we are nothing more than “little theologians.” He wouldn't criticize us for being more interested in the question “Who is the greatest among us?” than we are in the “plain and modest question about the matter at hand.” If he wasn't worried about the way we inflate ourselves by demeaning our rivals, he wouldn't ask why there are “so many really woeful theologians who go around with faces that are eternally troubled or even embittered, always in a rush to bring forward their critical reservations and negations?” And he wouldn't keep reminding us that evangelical theology is modest theology if he wasn't distressed by our immodesty—by the serenely confident way we make definitive pronouncements, even as we theoretically agree that all theological speech is limited and subject to revision. You don't write passages like the ones in this book unless you are concerned by how easily theologians confuse zealous pursuit of the truth with zealous pursuit of their own glory. It would not be far off to say that Barth's examination of this theme is something like a gloss on Jesus’s claim that you cannot simultaneously work for praise from God and praise from people. You can seek one or the other, but not both.

It is important to see that Barth is not taking cheap shots at theologians here. Yes, he is giving us strong medicine, but he is giving it to us because he thinks vanity turns us into the kind of people whose lives obscure the truth people who make the gospel less rather than more plausible. We cannot, of course, make the gospel less true. God is God, and the truth is the truth, and nothing we do can change that. But Barth understands the role that the existence of the community plays in both the perception and concealment of truth. “The community does not speak with words alone,” he writes. “It speaks by the very fact of its existence in the world.” There's what we say, and then there's who we are, and who we are says something.

And the connection with teaching is obvious. We believe that God sometimes uses flawed and sinful people like ourselves to make himself known. Since those are the only kind of people there are, those are the kind God uses. But how compelling could it possibly be for our students to hear us say, for example, that the Christian life is a life of self-giving that conforms to Jesus Christ's own life, or that the church lives to point away from itself to its Lord, when at the same time they see us carefully managing our CVs, ambitiously seeking acclaim and advancement, and morbidly competing with one another in exactly the same cutthroat ways that people in every academic discipline compete with one another? It doesn't add up. Arcade Fire is right: it’s absurd to trust a millionaire quoting the Sermon on the Mount. And it’s no less absurd for students to trust vain theologians when they talk about a crucified God.

I know this is not everyone's problem. Some readers don't need to hear this. They struggle with other vices. But anyone who has read the Gospels knows that Jesus goes out of his way to address this problem. Speaking specifically about teachers, he says, “They do all their deeds to be seen by others. . . . They love to have the place of honor at banquets and the best seats . . . and to be greeted with respect . . . and to have people call them [teacher]. . . . [But] the greatest among you will be your servant. All who exalt themselves will be humbled, and all who humble themselves will be exalted” (Matt. 23:1–12). In Luke 14 Jesus tells his disciples that following him requires giving up their possessions, and for many of us, the possession we covet most, the thing we cling to like greedy misers, is our reputation.

—Adam Neder, Theology as a Way of Life: On Teaching and Learning the Christian Faith (Baker Academic, 2019), 64-70

Four loves follow-up

A brief follow-up to the last post about the state of the four loves in the youngest generations today.

Consider the following portrait, all of whose modifiers are meant descriptively rather than critically or even pejoratively:

A man in his 20s or 30s who is godless, friendless, fatherless, childless, sexless, unmarried, and unpartnered, and who has no active relationship with a sibling, cousin, aunt, uncle, or grandparent. We will assume he is not motherless—everyone has (had) a mother—but we might also add that he lacks a healthy relationship with her or that he lives far away from her.

This, in extreme form, is the picture of loveless life I described in the last post, using the fourfold love popularized by C. S. Lewis: kinship, eros, friendship, and agape.

Here’s my question. In human history, apart from extreme crises brought about by natural disaster or famine or war or plague, has there even been a generation as full of such men (or women) as the present generation? The phenomenon is far from limited to “the West.” It includes Russia, Japan, and China, among others. Young people without meaningful relationships of any kind, anywhere on the grid of the four loves. They lack entirely the love of a god, the love of a spouse, the love of a child, the love of a friend, even the love of a parent.

On one hand, it seems I can’t go a day without reading a new story about this phenomenon; it’s on my mind this week because I just finished Joel Kotkin’s The Coming of Neo-Feudalism. Yet, on the other hand, the crisis we are facing seems so massive, so epochal, so devastating, so unprecedented, so complex, that in truth we can’t talk about it enough. We need to be shouting the problem aloud from the rooftops like a crazy end-times street preacher.

But what is to be done? That’s the question that haunts me. Whatever the answers, we should be laboring with all that we have to find them. The stakes are as high as they get.

Four loves loss

More than sixty year ago C. S. Lewis wrote a book called The Four Loves. Ever since, his framework has proven a reliable and popular paradigm for thinking about different aspects or modes of love. The terms he uses are storge, eros, philia, and agape; we might loosely translate these as kinship, romance, friendship, and self-giving to and for the other. They denote the love that obtains between members of a family, between spouses in a marriage, between close friends, and between humans and God.

More than sixty year ago C. S. Lewis wrote a book called The Four Loves. Ever since, his framework has proven a reliable and popular paradigm for thinking about different aspects or modes of love. The terms he uses are storge, eros, philia, and agape; we might loosely translate these as kinship, romance, friendship, and self-giving to and for the other. They denote the love that obtains between members of a family, between spouses in a marriage, between close friends, and between humans and God. (This last category is my own gloss; agape is, for Lewis and for the Christian tradition, the love God displays in Christ and thus the exemplary cause of both our love for him and our love for others.)

A thought occurred to me about these four loves, and I wonder if anyone else has written about it.

Our society is awash in loneliness, apathy, despair, and even sexlessness. The youngest generations (“Gen Z” and Millennials) are marrying later or not at all, and (thus) having fewer children or none at all. Divorce is rampant. Kin networks are declining in both quantity and quality, and what remains is fraying at the seams. Regular attendance of church (or synagogue, or mosque) reached historically low numbers before Covid; the pandemic has supercharged these trends beyond recognition. Even friendship, the last dependable and universal form of love, has seen drastic reductions, especially for men. I heard one sociologist, a middle-aged woman, remark recently that our young men are beset by “the three P’s: pot, porn, and PlayStation.” You can’t open an internet browser without stumbling upon the latest news report, study finding, or op-ed column on opioids, deaths of despair, hollowed-out factory towns, fatherless children, lethargic boys, screen-addled kids, housebound teens, risk-averse young adults, social awkwardness, and all the other symptoms of a sad, isolated, and unloved generation. They are like a car alarm ringing through the night. Eventually you get used to it and go back to sleep.

I don’t have anything especially insightful to say about any of this. But I found that, as Lewis’s book came to mind in conjunction with these trends, his framework suggested itself as a useful analytical grid. Perhaps one way to judge whether an individual is flourishing today is whether she can point confidently to the presence of all four loves in her life. A dense and supportive familial network of parents, grandparents, siblings, cousins, aunts, and uncles; a spouse and children of her own; concentric circles of friends who know her well, whom she sees regularly in a variety of settings, and on whom she can rely; a church to she belongs and where she consistently worships and enjoys the presence of the God who created her and continues to sustain her, day by day.