Resident Theologian

About the Blog

2021: the year of Martin, Rothfuss, and Williams?

Could 2021 see the publication of long-awaited sequels to three major fantasy series?

Could 2021 see the publication of long-awaited sequels to three major fantasy series?

It would mark a full decade since George R. R. Martin published the fifth entry in his Song of Ice and Fire. He's been writing pages and pages since then, or so he says. He turns 72 this month, and following the TV adaptation of Game of Thrones concluded, then living through a global pandemic, he's had nothing but time to write. In any case, even after #6, he's got at least one more book in the series to write, assuming it doesn't keep multiplying and fracturing indefinitely. One can hope, no?

It's also been a decade since the second book in Patrick Rothfuss's Kingkiller Chronicle trilogy was published. Four years spanned the first two books. Perhaps ten will span the second and the third? Rothfuss insists that he is hard at work on The Doors of Stone, yet reacts cantankerously to continuous "Are you finished yet?" queries. It's unclear whether it's the perfectionist in him or whether, like Martin, the sprawl of the story plus the lure of other projects is keeping completion just over the horizon.

Speaking of completion: A full three decades ago Tad Williams published his extraordinary trilogy Memory, Sorrow, and Thorn. He sat on it, sat on it, and sat on it some more—then finally made good on some hints and gestures in the closing pages of the final volume, To Green Angel Tower, with the publication in 2017 of a "bridge novel," The Heart of What Was Lost (a more Williams-esque title there never was, plangent and grand in epic lament as so much of his work is). Thus began a new trilogy, The Last King of Osten Ard, with volumes published in orderly sequence: 2017, 2019, and, in prospect, October 2021. (A second short prequel novel will be published in the summer.) Once he breaks the story, the man knows how to tell it, and how to finish it.

In sum, these are three great fantasy novelists working to complete three much-beloved fantasy series. And we could have all three authors publishing eagerly anticipated books in the next 15 months. Let it be so!

Louis Dupré on symbolism and ontology in religious language

Religious language must, by its very nature, be symbolic: its referent surpasses the objective universe. Objectivist language is fit only to signify things in a one-dimensional universe. It is incapable of referring to another level of reality, as art, poetry, and religion do.

Religious language must, by its very nature, be symbolic: its referent surpasses the objective universe. Objectivist language is fit only to signify things in a one-dimensional universe. It is incapable of referring to another level of reality, as art, poetry, and religion do. Rather than properly symbolizing, it establishes external analogies between objectively conceived realities. Their relation is allegorical rather than symbolic. A truly symbolic relation must be grounded in Being itself. Nothing exposes our religious impoverishment more directly than the loss of the ontological dimension of language. To overcome this, poets and mystics have removed their language as far as possible from everyday speech.

In premodern traditions, language remained closer to the ontological core which all things share and which intrinsically links them to one another. Symbols thereby participated in the very Being of what they symbolized, as they still do in great poetry. Religious symbols re-presented the divine reality: they actually made the divine present in images and metaphors. The ontological richness of the participatory presence of a truly symbolic system of signification appeared in the original conception of sacraments, rituals, icons, and ecclesiastical hierarchies.

The nominalism of the late Middle Ages resulted in a very different representation of the creature's relation with God. The world no longer appears as a divine expression except in the restricted sense of expressing the divine will. Finite reality becomes separated from its Creator. As a result, creatures have lost not only their intrinsic participation in God's Being but also their ontological communion with one another. Their relation becomes defined by divine decree. Nominalism not only has survived the secularization of modern thought, but has became radicalized in our own cybernetic culture, where symbols are reduced to arbitrary signs in an intramundane web of references, of which each point can be linked to any other point. The advantages of such a system need no proof: the entire scientific and technical functioning of contemporary society depends on it. At the same time, the modern mind's capacity for creating and understanding religious symbols has been severely weakened. Symbols have become man-made, objective signs, serviceable for making any reality part of a system without having to be part of that reality.

Recent theologians have attempted to stem the secular tide. Two of them did so by basically rethinking the relation between nature and grace, the main causes of today's secularism. Henri de Lubac undertook a historical critique of the modern separation of nature and supernatural. Not coincidentally, he also wrote a masterly literary study on religious symbolism before the nominalist revolution. In a number of works Hans Urs von Balthasar developed a theology in which grace, rather than being added to nature as a supernatural accident, constitutes the very depth of the mystery of Being. Being is both immanent and transcendent. Grace consists in its transcendent dimension. Whenever a poet, artist, or philosopher penetrates into the mystery of existence, he or she reveals an aspect of divine grace. Not only theology but also art and poetry, even philosophy, thereby regain a mystical quality, and religion resumes its place at the heart of human reality.

No program of theological renewal can by itself achieve a religious restoration. To be effective a theological vision requires a recognition of the sacred. Is the modern mind still capable of such a recognition? Its fundamental attitude directly conflicts with the conditions necessary for it. First, some kind of moral conversion has become indispensable. The immediate question is not whether we confess a religious faith, or whether we live in conformity with certain religious norms, but whether we are of a disposition to accept any kind of theoretical or practical direction coming from a source other than the mind itself. Such a disposition demands that we be prepared to abandon the conquering, self-sufficient state of mind characteristic of late modernity. I still believe in the necessity of what I wrote at an earlier occasion: "What is needed is a conversion to an attitude in which existing is more than taking, acting more than making, meaning more than function—an attitude in which there is enough leisure for wonder and enough detachment for transcendence. What is needed most of all is an attitude in which transcendence can be recognized again."

—Louis Dupré, Religion and the Rise of Modern Culture (2008), 115-117

François Furet on revolutionary consciousness

[T]he revolutionary situation was not only characterised by the power vacuum that was filled by a rush of new forces and by the 'free' activity of society. . . . It was also bound up with a kind of hypertrophy of historical consciousness and with a system of symbolic representations shared by the social actors.

[T]he revolutionary situation was not only characterised by the power vacuum that was filled by a rush of new forces and by the 'free' activity of society. . . . It was also bound up with a kind of hypertrophy of historical consciousness and with a system of symbolic representations shared by the social actors. The revolutionary consciousness, from 1789 on, was informed by the illusion of defeating a State that had already ceased to exist, in the name of a coalition of good intentions and of forces that foreshadowed the future. From the very beginning it was ever ready to place ideas above actual history, as if it were called upon to restructure a fragmented society by means of its own concepts. Repression became intolerable only when it became ineffectual. The Revolution was the historical space that separated two powers, the embodiment of the idea that history is shaped by human action rather than by the combination of existing institutions and forces.

In that unforeseeable and accelerated drift, the idea of human action patterned its goals on the exact opposite of the traditional principles underlying the social order. The Ancien Régime had been in the hands of the king; the Revolution was the people's achievement. France had been a kingdom of subjects; it was now a nation of citizens. The old society had been based on privilege; the Revolution established equality. Thus was created the ideology of a radical break with the past, a tremendous cultural drive for equality. Henceforth everything - the economy, society and politics - yielded to the force of ideology and to the militants who embodied it; no coalition nor any institution could last under the onslaught of that torrential advance.

Here I am using the term ideology to designate the two sets of beliefs that, to my mind, constitute the very bedrock of revolutionary consciousness. The first is that all personal problems and all moral or intellectual matters have become political; that there is no human misfortune not amenable to a political solution. The second is that, since everything can be known and changed, there is a perfect fit between action, knowledge and morality. That is why the revolutionary militants identified their private lives with their public ones and with the defence of their ideas. It was a formidable logic, which, in a laicised form, reproduced the psychological commitment that springs from religious beliefs. When politics becomes the realm of truth and falsehood, of good and evil, and when it is politics that separates the good from the wicked, we find ourselves in a historical universe whose dynamic is entirely new. As Marx realised in his early writings, the Revolution was the very incarnation of the illusion of politics: it transformed mere experience into conscious acts. It inaugurated a world that attributes every social change to known, classified and living forces; like mythical thought, it peoples the objective universe with subjective volitions, that is, as the case may be, with responsible leaders or scapegoats. In such a world, human action no longer encounters obstacles or limits, only adversaries, preferably traitors. The recurrence of that notion is a telling feature of the moral universe in which the revolutionary explosion took place.

No longer held together by the State, nor by the constraints that had been imposed by power and had masked its disintegration, society thus recomposed itself through ideology. Peopled by active volitions and recognising only faithful followers or adversaries, that new world had an incomparable capacity to integrate. It was the beginning of what has ever since been called 'politics', that is, a common yet contradictory language of debate and action around the central issue of power. The French Revolution, of course, did not 'invent' politics as an autonomous area of knowledge; to speak only of Christian Europe, the theory of political action as such dates back to Machiavelli, and the scholarly debate about the origin of society as an institution was well under way by the seventeenth century. But the example of the English Revolution shows that when it came to collective involvement and action, the fundamental frame of intellectual reference was still of a religious nature. What the French brought into being at the end of the eighteenth century was not politics as a laicised and distinct area of critical reflection but democratic politics as a national ideology. The secret of the success of 1789, its message and its lasting influence lie in that invention, which was unprecedented and whose legacy was to be so widespread. The English and French revolutions, though separated by more than a century, have many traits in common, none of which, however, was sufficient to bestow on the first the rôle of universal model that the second has played ever since it appeared on the stage of history. The reason is that Cromwell's Republic was too preoccupied with religious concerns and too intent upon its return to origins to develop the one notion that made Robespierre's language the prophecy of a new era: that democratic politics had come to decide the fate of individuals and peoples.

The term 'democratic politics' does not refer here to a set of rules or procedures designed to organise, on the basis of election results, the functioning of authority. Rather, it designates a system of beliefs that constitutes the new legitimacy born of the Revolution, and according to which the people', in order to establish the liberty and equality that are the objectives of collective action, must break its enemies' resistance. Having become the supreme means of putting values into action and the inevitable test of 'right' or 'wrong' will, politics could have only a public spokesman, in total harmony with those values, and enemies who remained concealed, since their designs could not be publicly admitted. The people were defined by their aspirations, and as an indistinct aggregate of individual 'right' wills. By that expedient, which precluded representation, the revolutionary consciousness was able to reconstruct an imaginary social cohesion in the name and on the basis of individual wills. That was its way of resolving the eighteenth century's great dilemma, that of conceptualising society in terms of the individual. If indeed the individual was defined in his every aspect by the aims of his political action, a set of goals as simple as a moral code would permit the Revolution to found a new language as well as a new society. Or, rather, to found a new society through a new language: today we would call that a nation; at the time it was celebrated in the fête de la Fédération.

—François Furet, Interpreting the French Revolution (trans. Elborg Forster; 1978), 25-27

10 thoughts on colleges reopening

1. Not every college is the same. There are community colleges, private colleges, public colleges. Some have 1,500 students, some have 50,000 students. Some are in rural areas and small towns, some are in densely populated urban centers. Some have wild and uncontrollable Greek life, some (very much) do not.

1. Not every college is the same. There are community colleges, private colleges, public colleges. Some have 1,500 students, some have 50,000 students. Some are in rural areas and small towns, some are in densely populated urban centers. Some have wild and uncontrollable Greek life, some (very much) do not.

2. Not every place is the same. There are regions, locales, and states that are still hot spots on lockdown, and there are others that are in rather better shape.

3. Not every institution is the same. Some are cash-strapped or risk-averse or profit-driven or top-down—or what have you—and some have resilient and time-honored habits of shared governance.

4. Not every professor is the same. This applies not only to characteristics like age or discipline but also to personal judgment or preference: universities are not split, in a perfect dichotomy, between administrators who are pushing forward with reopening and faculty who are pushing back.

5. Economic pressures are real. Although it is a sad and lamentable fact, American higher ed is a teetering tower ready to topple over at any moment. Without relitigating the relevant history, that is where things stand. Many, perhaps most, colleges were forced to make an impossible decision: reopen residential instruction, or initiate systematic lay-offs, firings, departmental cuts, and program eliminations. If the latter would have been truly unavoidable, how many staff and faculty would have opted to go fully online?

6. Students and families have agency. No one and nothing is forcing students to return to campus; if families preferred doing a gap year, getting a job, or learning online, there are readily available options for all three of those routes. Students and their families are making their own assessment of the risk. It is far from irrational to select residential college instruction, given the options.

7. Consider the alternatives for students. If a 20-year old who would be in college isn't in college, what is she doing? Either she is quarantined at home, working (likely not from home), or living it up with friends. The latter two options entail levels of risk commensurate with or far greater than residential college life. And the first follows on the heels of six full months of functional social lockdown, in the best of circumstances alone with a couple family members, in the worst trapped in dysfunctional households with negligent or unhealthy persons. We are only beginning to reckon with the effects of such extended isolation on young persons' mental health. In any case, there is no prefabricated universal calculus for what would be best for each person: continued isolation versus greater risk of exposure, and if the latter, at work or at college. Given the fact that so many families have chosen to send their children to college, shouldn't we presume a reasonable assessment of the risk and of the various options, and respect the possibility that such a decision was wise (or, again, the least bad choice, given the options)?

8. It follows from all of these reflections that there is no one-size-fits-all judgment upon "American colleges reopening." I have no doubt that some colleges should not have reopened; that some could have done so wisely but have not implemented adequate precautions; that some made the decision largely out of fear; that most did so as a financial necessity; that plenty did so cynically, hoping to make it long enough to capture non-refundable tuition. But those facts, in the aggregate, have little to say regarding particular cases; nor still do bad actors or even commonly held bad motivations per se mean that most colleges should not have reopened. The need for tuition and the precarity of jobs, on the one hand, and the rational desire of families to have a residential college to send their children to, on the other, can all coexist together.

9. What has been ascendant these last few months is a species of scientism that supposes questions of politics and prudence can be answered by experts in epidemiology and pandemics. But they cannot. What is needed instead is wisdom, the virtue of phronesis that puts practical reason to work in making global judgments, in light of all the evidence and the totality of factors, about what is best to be done in this case for this person for these reasons. Those reasons cannot be put under a microscope or studied in a lab. They are not verifiable. But resort to them is what is sorely needed in this moment.

10. In addition to wisdom, what we need is grace. Prudence can be applied differently; different people come to opposed judgments, either about distinct cases or about the same one. That is okay. We can live with that. I understand and respect those friends and writers and fellow academics who think reopening is foolhardy or unwise; I know they have their reasons. But such a judgment, even if correct, is not self-evident or uncontested. We have to have grace with one another, we have to learn how to be patient. I myself am impatient in the extreme. We have to try nonetheless (I have to try). That's the only way we're going to get through this together.

David Walker on slavery and the justice of God

And as the inhuman system of slavery, is the source from which most of our miseries proceed, I shall begin with that curse to nations, which has spread terror and devastation through so many nations of antiquity, and which is raging to such a pitch at the present day in Spain and in Portugal.

And as the inhuman system of slavery, is the source from which most of our miseries proceed, I shall begin with that curse to nations, which has spread terror and devastation through so many nations of antiquity, and which is raging to such a pitch at the present day in Spain and in Portugal. It had one tug in England, in France, and in the United States of America; yet the inhabitants thereof, do not learn wisdom, and erase it entirely from their dwellings and from all with whom they have to do. The fact is, the labour of slaves comes so cheap to the avaricious usurpers, and is (as they think) of such great utility to the country where it exists, that those who are actuated by sordid avarice only, overlook the evils, which will as sure as the Lord lives, follow after the good. In fact, they are so happy to keep in ignorance and degradation, and to receive the homage and the labour of the slaves, they forget that God rules in the armies of heaven and among the inhabitants of the earth, having his ears continually open to the cries, tears and groans of his oppressed people; and being a just and holy Being will at one day appear fully in behalf of the oppressed, and arrest the progress of the avaricious oppressors; for although the destruction of the oppressors God may not effect by the oppressed, yet the Lord our God will bring other destructions upon them—for not unfrequently will he cause them to rise up one against another, to be split and divided, and to oppress each other, and sometimes to open hostilities with sword in hand. Some may ask, what is the matter with this united and happy people?—Some say it is the cause of political usurpers, tyrants, oppressors, &c. But has not the Lord an oppressed and suffering people among them? Does the Lord condescend to hear their cries and see their tears in consequence of oppression? Will he let the oppressors rest comfortably and happy always? Will he not cause the very children of the oppressors to rise up against them, and oftimes put them to death? "God works in many ways his wonders to perform."

—David Walker's Appeal, in Four Articles; Together with a Preamble, to the Coloured Citizens of the World, But in Particular, and Very Expressly, to Those of the United States of America (1829), from the Preamble

Tony Judt on the New Left in the '60s

It was a curiosity of the age that the generational split transcended class as well as national experience. The rhetorical expression of youthful revolt was, of course, confined to a tiny minority: even in the US in those days, most young people did not attend university and college protests did not necessarily represent youth at large. But the broader symptoms of generational dissidence—music, clothing, language—were unusually widespread thanks to television, transistor radios and the internationalization of popular culture. By the late ’60s, the culture gap separating young people from their parents was perhaps greater than at any point since the early 19th century.

This breach in continuity echoed another tectonic shift. For an older generation of left-leaning politicians and voters, the relationship between ‘workers’ and socialism—between ‘the poor’ and the welfare state—had been self-evident. The ‘Left’ had long been associated with—and largely dependent upon— the urban industrial proletariat. Whatever their pragmatic attraction to the middle classes, the reforms of the New Deal, the Scandinavian social democracies and Britain’s welfare state had rested upon the presumptive support of a mass of blue collar workers and their rural allies.

But in the course of the 1950s, this blue collar proletariat was fragmenting and shrinking. Hard graft in traditional factories, mines and transport industries was giving way to automation, the rise of service industries and an increasingly feminized labor force. Even in Sweden, the social democrats could no longer hope to win elections simply by securing a majority of the traditional labor vote. The old Left, with its roots in working class communities and union organizations, could count on the instinctive collectivism and communal discipline (and subservience) of a corralled industrial work force. But that was a shrinking percentage of the population.

The new Left, as it began to call itself in those years, was something very different. To a younger generation, ‘change’ was not to be brought about by disciplined mass action defined and led by authorized spokesmen. Change itself appeared to have moved on from the industrial West into the developing or ‘third’ world. Communism and capitalism alike were charged with stagnation and ‘repression’. The initiative for radical innovation and action now lay either with distant peasants or else with a new set of revolutionary constituents. In place of the male proletariat there were now posited the candidacies of ‘blacks’, ‘students’, ‘women’ and, a little later, homosexuals.

Since none of these constituents, at home or abroad, was separately represented in the institutions of welfare societies, the new Left presented itself quite consciously as opposing not merely the injustices of the capitalist order but above all the ‘repressive tolerance’ of its most advanced forms: precisely those benevolent overseers responsible for liberalizing old constraints or providing for the betterment of all.

Above all, the new Left—and its overwhelmingly youthful constituency—rejected the inherited collectivism of its predecessor. To an earlier generation of reformers from Washington to Stockholm, it had been self-evident that ‘justice’, ‘equal opportunity’ or ‘economic security’ were shared objectives that could only be attained by common action. Whatever the shortcomings of over-intrusive top-down regulation and control, these were the price of social justice—and a price well worth paying.

A younger cohort saw things very differently. Social justice no longer preoccupied radicals. What united the ’60s generation was not the interest of all, but the needs and rights of each. ‘Individualism’—the assertion of every person’s claim to maximized private freedom and the unrestrained liberty to express autonomous desires and have them respected and institutionalized by society at large—became the left-wing watchword of the hour. Doing ‘your own thing’, ‘letting it all hang out’, ‘making love, not war’: these are not inherently unappealing goals, but they are of their essence private objectives, not public goods. Unsurprisingly, they led to the widespread assertion that ‘the personal is political’.

The politics of the ’60s thus devolved into an aggregation of individual claims upon society and the state. ‘Identity’ began to colonize public discourse: private identity, sexual identity, cultural identity. From here it was but a short step to the fragmentation of radical politics, its metamorphosis into multiculturalism. Curiously, the new Left remained exquisitely sensitive to the collective attributes of humans in distant lands, where they could be gathered up into anonymous social categories like ‘peasant’, ‘post-colonial’, ‘subaltern’ and the like. But back home, the individual reigned supreme.

However legitimate the claims of individuals and the importance of their rights, emphasizing these carries an unavoidable cost: the decline of a shared sense of purpose. Once upon a time one looked to society—or class, or community—for one’s normative vocabulary: what was good for everyone was by definition good for anyone. But the converse does not hold. What is good for one person may or may not be of value or interest to another. Conservative philosophers of an earlier age understood this well, which was why they resorted to religious language and imagery to justify traditional authority and its claims upon each individual.

But the individualism of the new Left respected neither collective purpose nor traditional authority: it was, after all, both new and left. What remained to it was the subjectivism of private—and privately-measured—interest and desire. This, in turn, invited a resort to aesthetic and moral relativism: if something is good for me it is not incumbent upon me to ascertain whether it is good for someone else—much less to impose it upon them (“do your own thing”).

True, many radicals of the ’60s were quite enthusiastic supporters of imposed choices, but only when these affected distant peoples of whom they knew little. Looking back, it is striking to note how many in western Europe and the United States expressed enthusiasm for Mao Tse-tung’s dictatorially uniform ‘cultural revolution’ while defining cultural reform at home as the maximizing of private initiative and autonomy.

In distant retrospect it may appear odd that so many young people in the ’60s identified with ‘Marxism’ and radical projects of all sorts, while simultaneously disassociating themselves from conformist norms and authoritarian purposes. But Marxism was the rhetorical awning under which very different dissenting styles could be gathered together—not least because it offered an illusory continuity with an earlier radical generation. But under that awning, and served by that illusion, the Left fragmented and lost all sense of shared purpose.

On the contrary, ‘Left’ took on a rather selfish air. To be on the Left, to be a radical in those years, was to be self-regarding, self-promoting and curiously parochial in one’s concerns. Left-wing student movements were more preoccupied with college gate hours than with factory working practices; the university-attending sons of the Italian upper-middle-class beat up underpaid policemen in the name of revolutionary justice; light-hearted ironic slogans demanding sexual freedom displaced angry proletarian objections to capitalist exploiters. This is not to say that a new generation of radicals was insensitive to injustice or political malfeasance: the Vietnam protests and the race riots of the ’60s were not insignificant. But they were divorced from any sense of collective purpose, being rather understood as extensions of individual self-expression and anger.

These paradoxes of meritocracy—the ’60s generation was above all the successful byproduct of the very welfare states on which it poured such youthful scorn—reflected a failure of nerve. The old patrician classes had given way to a generation of well-intentioned social engineers, but neither was prepared for the radical disaffection of their children. The implicit consensus of the postwar decades was now broken, and a new, decidedly unnatural consensus was beginning to emerge around the primacy of private interest. The young radicals would never have described their purposes in such a way, but it was the distinction between praiseworthy private freedoms and irritating public constraints which most exercised their emotions. And this very distinction, ironically, described the newly emerging Right as well.

—Tony Judt, Ill Fares the Land (2010), pp. 85-91

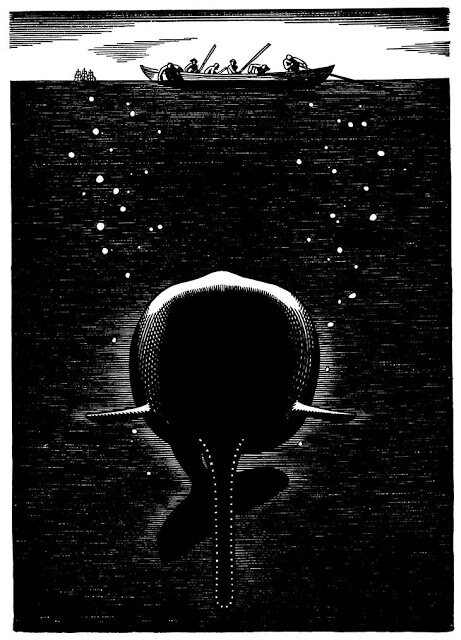

Ahab, slave to the dread tyrant Sin: Melville's dramatic exegesis of Romans 7

Near the finale of Moby-Dick, in the closing moments of the last chapter before the great chase for the white whale begins, gloomy Ahab has one final heartfelt conversation with Starbuck, his earnest and home-loving first mate. At the very moment when the climactic encounter is nigh, Ahab looks to pull back. And Starbuck is eager to help him do so. They converse on the deck, Ahab unsure of himself and Starbuck pleading with him, wooing him, conjuring the decision against the fatal hunt that he so hopes Ahab is capable of making. And just when Starbuck thinks he has his quarry, something inexplicable and wholly mysterious changes in Ahab. Here is Melville:

But Ahab's glance was averted; like a blighted fruit tree he shook, and cast his last, cindered apple to the soil.

"What is it, what nameless, inscrutable, unearthly thing is it; what cozening, hidden lord and master, and cruel, remorseless emperor commands me; that against all natural lovings and longings, I so keep pushing, and crowding, and jamming myself on all the time; recklessly making me ready to do what in my own proper, natural heart, I durst not so much as dare? Is it Ahab, Ahab? Is it I, God, or who, that lifts this arm? But if the great sun move not of himself; but is as an errand-boy in heaven; nor one single star can revolve, but by some invisible power; how then can this one small heart beat; this one small brain think thoughts; unless God does that beating, does that thinking, does that living, and not I. By heaven, man, we are turned round and round in this world, like yonder windlass, and Fate is the handspike. And all the time, lo! that smiling sky, and this unsounded sea! Look! see yon Albicore! who put it into him to chase and fang that flying-fish? Where do murderers go, man! Who's to doom, when the judge himself is dragged to the bar? But it is a mild, mild wind, and a mild looking sky; and the air smells now, as if it blew from a far-away meadow; they have been making hay somewhere under the slopes of the Andes, Starbuck, and the mowers are sleeping among the new-mown hay. Sleeping? Aye, toil we how we may, we all sleep at last on the field. Sleep? Aye, and rust amid greenness; as last year's scythes flung down, and left in the half-cut swaths—Starbuck!"

Melville is playing out for us here, in dramatic form, the similar soliloquy of St. Paul in chapter 7 of his epistle to the Romans:

I do not understand my own actions. For I do not do what I want, but I do the very thing I hate. Now if I do what I do not want, I agree that the law is good. So then it is no longer I that do it, but sin which dwells within me. For I know that nothing good dwells within me, that is, in my flesh. I can will what is right, but I cannot do it. For I do not do the good I want, but the evil I do not want is what I do. Now if I do what I do not want, it is no longer I that do it, but sin which dwells within me. So I find it to be a law that when I want to do right, evil lies close at hand. (vv. 15-21)

The "old man" weighed down by the flesh, Adam in his chains, lies in the squalor of bondage to sin—not just his own sins, but Sin, a sort of emergent personified power, a tyrant who reigns over the fallen children of Adam. Such a one is by definition unfree, and therefore utterly unfree even to choose the good, and therefore absolutely incapable of saving himself. Even with the wise route laid out before him, he cannot act. He needs a savior and more than a savior: a rival king to trample down Sin's false kingdom, and together with him to put to Death to death.

So argues Matthew Croasmun in his book The Emergence of Sin: The Cosmic Tyrant in Romans. (See further Wesley Hill's stimulating reflections on the book.) Ahab exemplifies Croasmun's thesis.

But because Melville is Melville, he's up to even more. Notice the brief, seemingly throwaway prefatory line of poetic simile: "But Ahab's glance was averted; like a blighted fruit tree he shook, and cast his last, cindered apple to the soil." Melville knows he's depicting the old man; he knows he writes of Adam. That is why he places us in a garden with a spoiled tree with its spoiled fruit "cast"—fallen—to the "soil"—adamah. And it is why, finally, he begins with the gaze: "Ahab's glance was averted." As St. Augustine writes in Book XIV of City of God, the sin of Adam was not per se the eating of the fruit of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil; evil acts come from an evil will. (Augustine quotes Jesus from the Sermon on the Mount to note that evil fruit could only come—metaphorically—from an evil tree—the will of the first man.) Whence Adam's evil will, then? There is no trite answer, no easy explanation. In chapter 13 Augustine spells out the logic (italics all mine):

Our first parents fell into open disobedience because already they were secretly corrupted; for the evil act had never been done had not an evil will preceded it. And what is the origin of our evil will but pride? For "pride is the beginning of sin" (Sirach 10:13). And what is pride but the craving for undue exaltation? And this is undue exaltation, when the soul abandons Him to whom it ought to cleave as its end, and becomes a kind of end to itself. This happens when it becomes its own satisfaction. And it does so when it falls away from that unchangeable good which ought to satisfy it more than itself. This falling away is spontaneous; for if the will had remained steadfast in the love of that higher and changeless good by which it was illumined to intelligence and kindled into love, it would not have turned away to find satisfaction in itself, and so become frigid and benighted; the woman would not have believed the serpent spoke the truth, nor would the man have preferred the request of his wife to the command of God, nor have supposed that it was a venial transgression to cleave to the partner of his life even in a partnership of sin. The wicked deed, then—that is to say, the transgression of eating the forbidden fruit—was committed by persons who were already wicked.

Evil acts have their source in an evil will, and a will becomes evil when it becomes uncoupled from its true end and finds its end in itself. To become one's own end is to fall away from the true and eternal Good that alone satisfies the longings of the soul. "This falling away is spontaneous": there is no narrative, no logic, no inner rationale much less necessity, that can account for it. It just happens. The image Augustine uses for this spontaneous falling is "turning away," depicted as a kind of anti-repentance. Adam turns his eyes from God, his final End and supreme Good, to lesser things. Doing so just is The Fall.

And that is just what Melville his his Adam, Ahab, do in response to Starbuck's eminently reasonable efforts to persuade: "But Ahab's glance was averted." By what? To what? Why? We aren't told. It's spontaneous; there is no explanation to be sought because there is no explanation to be had. Ahab's turn is a surd like all sin is a surd. It has no reason, for it is no-reason, not-reason incarnate. His desire has overwhelmed his sense; his craving has overtaken his will; he himself has become his own end, and answering the command of another, from without, he rushes to his fate "against all natural lovings and longings," no matter the cost, his own life and the life of his men be damned.

Damned, indeed. Ahab is Adam without a second Adam. There is no savior in his story, even if Starbuck stands in for one as a kind of messenger or angel. Ahab, that archetypal self-made American man, is finally not the captain of his own ship. The captain of the Pequod is rather that "cozening, hidden lord and master, and cruel, remorseless emperor" in whose service Ahab places himself when he baptizes the barb meant for the white whale: "Ego non baptizo te in nomine patris, sed in nomine diaboli."

The devil is Ahab's lord, as he is fallen Adam's master. He reigns in their death-bound lives through their bent and broken wills by the tyrannical power of Sin. Absent intervention, Adam's fate is Ahab's: to be drowned eternally in the depths of the sea, bound by the lines of his own consecrated weaponry to the impervious hide of Leviathan: the very object to which his gaze turned, the means of his helpless demise.

Wallace Stegner on the writing life of academic overachievers

I remember little about Madison as a city, have no map of its streets in my mind, am rarely brought up short by remembered smells or colors from that time. I don’t even recall what courses I taught. I really never did live there, I only worked there. I landed working and never let up.

What I was paid to do I did conscientiously with forty percent of my mind and time. A Depression schedule, surely—four large classes, whatever they were, three days a week. Before and between and after my classes, I wrote, for despite my limited one-year appointment I hoped for continuance, and I did not intend to perish for lack of publications. I wrote an unbelievable amount, not only what I wanted to write but anything any editor asked for—stories, articles, book reviews, a novel, parts of a textbook. Logorrhea. A scholarly colleague, one of those who spent two months on a two-paragraph communication to Notes and Queries and had been working for six years on a book that nobody would ever publish, was heard to refer to me as the Man of Letters, spelled h-a-c-k. His sneer so little affected me that I can’t even remember his name.

Nowadays, people might wonder how my marriage lasted. It lasted fine. It throve, partly because I was as industrious as an anteater in a termite mound and wouldn’t have noticed anything short of a walkout, but more because Sally was completely supportive and never thought of herself as a neglected wife—“thesis widows,” we used to call them in graduate school. She was probably lonely for the first two or three weeks. Once we met the Langs she never had time to be, whether I was available or not. It was a toss-up who was neglecting whom.

Early in our time in Madison I stuck a chart on the concrete wall of my furnace room. It reminded me every morning that there are one hundred sixty-eight hours in a week. Seventy of those I dedicated to sleep, breakfasts, and dinners (chances for socializing with Sally in all of those areas). Lunches I made no allowance for because I brown-bagged it at noon in my office, and read papers while I ate. To my job—classes, preparation, office hours, conferences, paper-reading—I conceded fifty hours, though when students didn’t show up for appointments I could use the time for reading papers and so gain a few minutes elsewhere. With one hundred and twenty hours set aside, I had forty-eight for my own. Obviously I couldn’t write forty-eight hours a week, but I did my best, and when holidays at Thanksgiving and Christmas gave me a break, I exceeded my quota.

Hard to recapture. I was your basic overachiever, a workaholic, a pathological beaver of a boy who chewed continually because his teeth kept growing. Nobody could have sustained my schedule for long without a breakdown, and I learned my limitations eventually. Yet when I hear the contemporary disparagement of ambition and the work ethic, I bristle. I can’t help it.

I overdid, I punished us both. But I was anxious about the coming baby and uncertain about my job. I had learned something about deprivation, and I wanted to guarantee the future as much as effort could guarantee it. And I had been given, first by Story and then by the Atlantic, intimations that I had a gift.

Thinking about it now, I am struck by how modest my aims were. I didn’t expect to hit any jackpots. I had no definite goal. I merely wanted to do well what my inclinations and training led me to do, and I suppose I assumed that somehow, far off, some good might flow from it. I had no idea what. I respected literature and its vague addiction to truth at least as much as tycoons are supposed to respect money and power, but I never had time to sit down and consider why I respected it.

Ambition is a path, not a destination, and it is essentially the same path for everybody. No matter what the goal is, the path leads through Pilgrim’s Progress regions of motivation, hard work, persistence, stubbornness, and resilience under disappointment. Unconsidered, merely indulged, ambition becomes a vice; it can turn a man into a machine that knows nothing but how to run. Considered, it can be something else—pathway to the stars, maybe.

I suspect that what makes hedonists so angry when they think about overachievers is that the overachievers, without drugs or orgies, have more fun.

—Wallace Stegner, Crossing to Safety (1987), pp. 96–98

On finding race and racism in the New Testament

I am skeptical of attempts to center contemporary Christian conversations about race on New Testament texts purported to feature or critique racism. From what I can tell, this move is a common one. Pericopes adduced include Jesus's encounter with the Syro-Phoenician woman, his meeting with the Samaritan woman at the well, and the parable of the good Samaritan. Most often, however, I see writers, pastors, and preachers use the example of gentiles in the early Jewish church, deploying some combination of Acts 15, Ephesians 2, Galatians, and Romans in order to illustrate the ostensible overcoming of racism in the early Jesus movement as an abiding example for churches struggling with the same problem today.

Why am I skeptical of this move? Let me try to spell out my reasons succinctly.

1. Race is a modern construct. What we mean by "race" does not exist in the New Testament, either as a concept or as a narratively depicted phenomenon.

2. Racism, therefore, also does not exist in the New Testament. I'm a defender of theological anachronism in Christian exegesis of Scripture, but speaking of "racism in the New Testament" is the worst kind of anachronism. It's a projection without a backdrop, a house built on sand, a conclusion in search of an argument.

3. Prejudice toward, suspicion of, and stereotyping of persons from other communities—where "other" denotes differences in region, language, cult, class, or scriptural interpretation—did exist in the eastern Mediterranean world of the Roman Empire in the first century. Inasmuch as contemporary readers want to draw analogies between forms of modern prejudice and forms of ancient prejudice, as the latter is found in the New Testament, so be it.

4. It is a fearful and perilous thing, however, to attribute such prejudice to those Jews who populated the early church or who opposed it. Why? First of all, because today it is almost uniformly gentiles who make this claim, and gentile Christians have an almost ineradicable propensity to assign to Jews—past and present—sinful behavior they seek to expunge in themselves. (See also #7 and #10 below.)

5. Moreover, Jewish attitudes about gentiles in the first century were neither uniform nor simple nor reducible to prejudice. The principal thing to realize is that, according to the witness of both the prophets and the apostles (that is, the Old and New Testaments), the distinction between Jews and gentiles is a creation of God. There are Jews and gentiles because God called Abraham and all his descendants with him to be set apart as God's holy people. All those not so called, according to the flesh, are gentiles. This distinction is maintained, not abolished, in the preaching of the gospel by the Jewish apostles in the first half century of the church's existence.

6. First-century Jewish beliefs about and relations with gentiles, then, were informed by scriptural testimony. God's word—that is, the Law, the prophets, and the writings—has a lot to say, after all, about the nations (the goyim or ethne). Go read some of it. See if you walk away with a clear, obvious, and uncomplicated view about those human communities that lie outside the election of Abraham together with his seed. Focus in particular on the book of Leviticus. Then go read chapter 10 of the book of Acts. Is St. Peter blameworthy for his hesitancy about Cornelius and his household? Is he foolish or shortsighted, much less prejudiced? Or is he following the way the words run in the Torah until such time as an angel of the Lord Jesus provides a vision paired with a divine command to act according to an alternative and heretofore unimagined interpretation of Torah? (An interpretation, note, only possible now in the light of the resurrection of the Messiah from the dead.) I'd say it's fair to think Peter, along with his brother apostles, was not in the wrong if God deemed a vision necessary to change his mind—a vision, mind you, that is didactic, not an indictment.

(7. As a historical matter, it is also worth drawing attention to the work of scholars precisely on persons such as Cornelius, gentile God-fearers and friends and patrons of the synagogue in the diaspora. The caricature of Jews living outside the land in the first century, distributed across countless cities in the Roman Empire and elsewhere, as bitter, sectarian, resentful, fearful, and hostile ethnic fundamentalists is just that: a caricature. Indeed, one should always beware of anti-Jewish sentiment lingering just beneath and sometimes displayed right on the surface of historical scholarship as well as popularized historical treatments of the Bible.)

8. As for Acts 15—the culmination, as St. Luke tells it, of Peter's vision, of Saul's conversion, of Pentecost, of the ascension, of the birth of Jesus, in fact of the calling of Abraham and the creation of Adam—the story is hardly one of racism or even of ethnic prejudice. The question for the nascent apostolic church was not whether gentiles could join. It would certainly qualify as something akin to ethnic prejudice if the exclusively Jewish ekklesia said, "We don't want your kind here." But that's not what they said. All saw and glorified God for the wonders he'd worked among the gentiles, drawing them to faith in Jesus Messiah. The question—the only question—was on what terms they would enter, that is, by what means and in accordance with what rule of life they would become members of Christ's body. Would they, like the Jews, follow the Law of Moses? Would they honor the Sabbath, keep kosher, be circumcised? Or would they not?—that is, by remaining gentiles, not subject to Torah's statutes and ordinances. Either way, they would be saved; either way, they would believe in Jesus; either way, they would receive baptism and thereby Jesus's own Spirit. The issue, in short, was not an ethnic, much less a racial, one. The issue was the will of God for those believers in Jesus who were not descendants of Abraham. And after not a little disputation and controversy, the apostolic church discerned that it was the Spirit's good pleasure for the church to comprise Jews and gentiles both, united in the Messiah as Jew and gentile, neither becoming the other nor both becoming a third thing.

9. It turns out, therefore, that the climactic tale of gentiles being welcomed into Jewish messianic assemblies around the Mediterranean Sea in the years 30–80 AD has nothing whatsoever to do with race, racism, or ethnic prejudice. Acts 15 is simply not about that. Insinuating that it does either distorts its proper significance or metaphorizes a text without grounding, or even the need, to do so.

10. None of the foregoing is meant to suggest that either the New or the Old Testament is thus reduced to silence on pressing challenges facing the American church today, not least the seemingly unexorcisable demon of anti-black racism. Nor, as I said above, is it impossible, or imprudent, to draw analogies between scriptural instances of out-group derogation and present-day experience, or between the complications arising from Jew-gentile integration in Pauline assemblies and similar complications in American churches. Nor, finally, does the wider witness of Holy Scripture have nothing to say about the bedrock principles that ought to inform Christian speech about these matters: that God is sovereign, gracious Creator of all; that every human being is created in the image of God; that each and every human being who has ever lived is one, in St. Paul's words, "for whom Christ died." I only want to emphasize what we can and what we cannot responsibly read the canon to say. More than anything, though, I want to encourage gentile Christians to be vigilant in their perpetual war against Marcionitism in all its forms. There is a worrisome tendency in recent Christian talk about white racism in America to frame it, biblically and theologically, as anticipated and foreshadowed by Jews. Even when unintended—and I have no doubt it usually is—that is a morally noxious, canonically warped, theologically obtuse, and historically false claim. The early Jewish church did not resist gentile inclusion due to its racism against gentiles. It had none, for there was none to have. There is, lamentably, plenty of racism in the world today. Look there if you want to address it. You won't find any in the pages of the Bible.

Covid, church closures, and three rationales for worship

Why do people go to church? Why do churches gather for worship on Sunday morning?

I've been asking myself this question in light of the lockdown and subsequent church closures and shifts to online streaming. And the question isn't theological so much as sociological.

After all, ordinary Christians don't go to church according to highly technical doctrinal articulations of the sort offered by systematic theologians. They have much more banal or quotidian or subjective reasons.

That's not to say those reasons aren't theological. Only that we shouldn't resort to high-level dogmatic language to explain lay folks' behavior or reasoning—or even local congregations' or parishes'. (In the case of the latter, the question isn't so much what they say explicitly but what their organization and enactment of worship "says"; what unspoken logic is embedded, implicit, in their actual liturgical practices.)

Part of the motive for thinking about this concerns the other side of society-wide lockdowns: Why would or should churches reopen? How urgent is the need or desire to do so, at the objective or subjective level? What motivates individual members of churches to delay or hasten reopening?

Here's my answer. I think, broadly speaking, there are three inner rationales for American churches' gathering for worship: sacrament, fellowship, and experience. Let me unpack these briefly.

First is sacrament. This group comprises catholic and liturgical churches ordinarily led by priests: Anglican, Orthodox, Roman Catholic, perhaps Lutheran or even sometimes Methodist traditions. Why does one go to church? Why does the church gather? Among other reasons, to receive the holy sacrament. That is the thing, the sine qua non, of Christian worship. Moreover, one cannot partake of it anywhere else. To quarantine under lockdown is one and the same as to fast from the body and blood of Christ.

Second is fellowship. This group would likely cover every manner of church across nearly all denominations. I leave "fellowship" unqualified, since it can refer simultaneously to communion with God and with fellow believers. But the emphasis is on the fellow-feeling of being gathered together with sisters and brothers in the unity of the corporate body of Christ. Such fellow-feeling is far from a natural property or a mere subjective experience; it is a spiritual and communal fact: this body of believers, right here, assembled in this space, are the sign and site of God's presence in the world. Why gather, then? Among other reasons, to enact and participate in the fellowship that Christ's Spirit makes possible when disciples congregate to worship God and hear from his word.

Third is experience. This group includes those other Protestant and especially "low church" traditions that emphasize the subjective aspect of worship. Certainly these churches are going to trend charismatic and Pentecostal, but they also include decidedly non-charismatic evangelical and non-denominational churches that place a premium on the concert-level quality of the praise band's leading of Sunday morning worship. In many ways these churches put on a weekly performance, and what attendees come for is to experience that performance. (NB: The highest of high-church liturgy is also a kind of performance, indeed a kind of extended drama; so the term itself is neutral, not pejorative.) Believers in these traditions and congregations wake up on Sundays and gather with others in order to experience what can only be had then and there: the communal, emotional, and (sometimes) charismatic energy and power of the Holy Spirit at work in mighty ways to make known the promeity—the for-me-ness—of God's love in Christ.

Suppose this typology is near the mark. What then does it say about church closings and reopenings under Covid?

First, fellowship-churches have the least intrinsic urgency to reopen. Why? On the one hand, because however attenuated, worship from home is a possibility for such communities. On the other hand, because the very thing sought in assembled worship is supremely difficult to achieve in a pandemic; mandatory mask-wearing, social distancing, no hugging or coffee hour or any of the other common ways the body is built up—these all mitigate the possibility of fellowship, both horizontal and vertical, in the extreme.

Second, sacrament-churches have the strongest inner rationale to reopen, indeed never to have fully closed in the first place. Many priests have continued unceasingly to say Mass or lead the Divine Liturgy since March, sometimes alone, sometimes with deacons or assistants, sometimes with half a dozen or so parishioners. Why? Because God ought still to be worshiped in the appointed manner by his ordained servants who stand in for, which is to say represent, the people as a whole. And because there is no digital Eucharist, no streaming sacrament, no self-feeding or solo consecration available to believers at home. (Perhaps, in fact, they view from afar and receive the sanctified elements later that day, distributed by the priest to congregants in their homes.)

Third, experience-churches are in something of a bind. On the one hand, there is a sense in which church members can participate from home: if worship is akin to a musical (or didactic!) performance, then YouTube was made for such things. On the other hand, streaming a concert and attending one are two distinct experiences. So the longer the lockdown lasts, the stronger the desire to return to in-person worship. The question for leaders at such churches is fourfold, however. First, if you build it, will they come? That is, what if your people's cautions about Covid are greater than their subjective desire to have the experience? Second, what of health precautions in worship? It's difficult to have unfettered communal experience of the Spirit in accordance with CDC guidelines (a la fellowship-churches above). Should such precautions go to the wind, given the importance of worship, or no? Third, if a church's particular appeal is the quality of the experience it has to offer, what happens when (a) the experience is no longer there to be had and/or (b) onetime attendees do some digital church shopping and find superior experiences elsewhere? Relatedly, and last, what if such church-shoppers realize the experience isn't appreciably different at home, and that streaming worship from the comfort of one's home—at a time one chooses, in a medium one prefers, while eating a snack or wearing pajamas—is preferable to the analog rigors of actually getting up and going to a physical building with other people?

I know pastors, ministers, elders, and other church leaders are asking themselves these and many other questions. I don't envy them. But it's useful to realize that not all churches are the same; not every Christian or parish has the same inner rationale for gathering or regathering under ordinary, much less extraordinary, conditions. At the very least, it's going to be illuminating to see what the American church looks like on the other side of the pandemic.

On Moby-Dick

I finally did it. Last month I read Herman Melville's Moby-Dick.

It would be an understatement to say that I loved it. I fell in love. And with all of it: the prose, the themes, the characters, the plot, the figural saturation, the endless and endlessly digressive chapters, the sheer American mythic theogony of it.

When one commits to read such heralded classics, there's always the question lingering in the back of one's mind whether it will prove a crushing disappointment. Like meeting one's heroes, reading the canon is not always for the faint of heart.

No such disappointment with Moby-Dick. Since I started it, and especially since I finished it, I have been an annoying pest to anyone and everyone who will listen to me sing of its greatness, some 170 years since its writing.

The air one breathes while reading Melville is rare. It's the same air one discovers blowing through Shakespeare, Dante, Milton, Dostoevsky, Virgil, Homer. After reading such authors, one understands the true meaning of such over-used terms like "classic," "genius," and "master." They are a class unto themselves.

Reading Melville's writing in Moby-Dick is like reading Shakespeare, only if he were an American and wrote prose. It's poetry in long-form and without line breaks. Melville did not know how to write an uninteresting sentence. The cavalcade of words builds and builds until it becomes a vast and imposing army in flawless formation, executing whatever order of subtle wit or penetrating insight Melville deigned to issue.

Did I mention he's funny? Laugh out loud funny. Every sentence in the book could be underlined, every third paragraph circled and starred, every fifth excerpted in an anthology of nothing but samples of perfect instances of American English construction.

I got bit by the theology bug early in my teens. I was dead set on my discipline from an early age. But had I read Moby-Dick at the same age, they might have gotten me instead. I mean language and lit: I might have been bound for English departments, buried beneath a rubble of 19th century manuscripts, for the rest of my life. Indeed, what makes a classic a classic, and therefore what makes Melville's opus a classic, is its inexhaustible character. Upon closing the final page, I could imagine dedicating my life to this book and this book alone. Its riches are bottomless.

Yet the one thing I can't imagine is having anything original to say about such a widely interpreted and commented-upon book. Even these reflections are little more than modest variations on the same ringing theme common to thousands upon thousands of American readers since the centenary of Melville's birth in 1919. But I'm hungry for more. I already read Nathan Philbrick's Why Read Moby-Dick? Here's to more where that came from, and above all, to many, many, many re-readings of that great mythic tome—that oceanic mishmash of Qoheleth and the Book of Job—that biblical pastiche of the enduring American soul—the undoubted and unrivaled great American novel—the one, the only, Moby-Dick; or, The Whale.

On the historical present

Les Murray on love and forgiveness

Morality and legality, killing and murder

100 theologians before the 20th century

- St. Ignatius of Antioch (d. 108)

- St. Justin Martyr (100-165)

- St. Irenaeus of Lyons (c. 130-202)

- St. Clement of Alexandria (c. 150-215)

- Tertullian (c. 155-240)

- Origen (c. 184-253)

- St. Cyprian of Carthage (d. 258)

- Eusebius of Caesarea (265-339)

- St. Athanasius (c. 297-373)

10.

- St. Ephrem the Syrian (c. 306-373)

- St. Hilary of Poitiers (c. 315-368)

- St. Cyril of Jerusalem (c. 315-386)

- St. Basil the Great (c. 329-379)

- St. Gregory of Nazianzus (c. 330-390)

- St. Gregory of Nyssa (c. 335-395)

- St. Ambrose (c. 340-397)

- St. Jerome (c. 343-420)

- St. John Chrysostom (c. 347-407)

- St. Augustine of Hippo (c. 354-430)

- St. John Cassian (c. 360-435)

- St. Cyril of Alexandria (c. 376-444)

- St. Peter Chrysologus (c. 400-450)

- Pope St. Leo the Great (c. 400-461)

- St. Severinus Boethius (477-524)

- St. Gregory the Great (c. 540-604)

- St. Isidore of Seville (c. 560-636)

- Dionysius the Areopagite (c. 565-625)

- St. John Climacus (c. 579-649)

- St. Maximus the Confessor (c. 580-662)

- St. Isaac of Nineveh (c. 613-700)

- St. Bede the Venerable (c. 673-735)

- St. John Damascene (c. 675-749)

- Theodore Abu Qurrah (c. 750-820)

- St. Theodore of Studium (c. 759-826)

- St. Photius the Great (c. 810-893)

- John Scotus Eriugena (c. 815-877)

- St. Symeon the New Theologian (949-1022)

- St. Gregory of Narek (951-1003)

- St. Peter Damian (1007-1072)

- Michael Psellos (1017-1078)

- St. Anselm of Canterbury (1033-1109)

- Peter Abelard (c. 1079-1142)

- St. Bernard of Clairvaux (c. 1090-1153)

- Peter Lombard (c. 1096-1160)

- Hugh of St. Victor (c. 1096-1141)

- St. Hildegard of Bingen (1098-1179)

- Nicholas of Methone (1100-1165)

- Richard of St. Victor (1110-1173)

- Joachim of Fiore (c. 1135-1202)

- Alexander of Hales (1185-1245)

- St. Anthony of Padua (1195-1231)

- St. Albert the Great (c. 1200-1280)

- St. Bonaventure (c. 1217-1274)

- St. Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274)

- Meister Eckhart (c. 1260-1328)

- Dante Alighieri (c. 1265-1321)

- Bl. John Duns Scotus (1265-1308)

- William of Ockham (c. 1287-1347)

- Bl. John van Ruysbroeck (c. 1293-1381)

- Bl. Henry Suso (1295-1366)

- St. Gregory Palamas (c. 1296-1357)

- Johannes Tauler (1300-1361)

- St. Nicholas Kabasilas (1319-1392)

- John Wycliffe (c. 1320-1384)

- Julian of Norwich (c. 1343-1420)

- St. Catherine of Siena (c. 1347-1380)

- Jan Hus (c. 1372-1415)

- St. Symeon of Thessaloniki (c. 1381-1429)

- St. Mark of Ephesus (1392-1444)

- Nicholas of Cusa (1401-1464)

- Denys the Carthusian (1402-1471)

- Desiderius Erasmus (1466-1536)

- Thomas Cajetan (1469-1534)

- St. Thomas More (1478-1535)

- Balthasar Hubmaier (1480-1528)

- Martin Luther (1483-1546)

- Huldrych Zwingli (1484-1531)

- Bartolomé de las Casas (1484-1566)

- Thomas Müntzer (1489-1525)

- Thomas Cranmer (1489-1556)

- St. Ignatius of Loyola (1491-1556)

- Martin Bucer (1491-1551)

- Menno Simmons (1496-1561)

- Philip Melanchthon (1497-1560)

- Peter Martyr Vermigli (1499-1562)

- St. John of Ávila (1500-1569)

- Heinrich Bullinger (1504-1575)

- John Calvin (1509-1564)

- John Knox (1514-1572)

- St. Teresa of Ávila (1515-1582)

- Theodore Beza (1519-1605)

- St. Peter Canisius (1521-1597)

- Martin Chemnitz (1522-1586)

- Domingo Báñez (1528-1604)

- Zacharias Ursinus (1534-1583)

- Luis de Molina (1535-1600)

- St. John of the Cross (1542-1591)

- St. Robert Bellarmine (1542-1621)

- Francisco Suárez (1548-1617)

- Richard Hooker (1554-1600)

- Lancelot Andrewes (1555-1626)

- Johann Arndt (1555-1621)

- Johannes Althusius (1557-1638)

- William Perkins (1558-1602)

- St. Lawrence of Brindisi (1559-1619)

- Jacob Arminius (1560-1609)

- Amandus Polanus (1561-1610)

- St. Francis de Sales (1567-1622)

- Jakob Böhme (1575-1624)

- William Ames (1576-1633)

- Johann Gerhard (1582-1637)

- Meletios Syrigos (1585-1664)

- John of St Thomas (1589-1644)

- Samuel Rutherford (1600-1661)

- John Milton (1608-1674)

- John Owen (1616-1683)

- Francis Turretin (1623-1687)

- Petrus van Mastricht (1630-1706)

- Philipp Spener (1635-1705)

- Thomas Traherne (c. 1636-1674)

- Patriarch Dositheos II of Jerusalem (1641-1707)

- August Hermann Francke (1663-1727)

- St. Alphonsus Liguori (1696-1787)

- Nicolaus Zinzendorf (1700-1760)

- Jonathan Edwards (1703-1758)

- John Wesley (1703-1791)

- St. Nikodimos of the Holy Mountain (1749-1809)

- St. Seraphim of Sarov (1754-1833)

- Friedrich Schleiermacher (1768-1834)

- St. Philaret of Moscow (1782-1867)

- Ferdinand Christian Baur (1792-1860)

- Johann Adam Möhler (1796-1838)

- Charles Hodge (1797-1878)

- St. John Henry Newman (1801-1890)

- John Williamson Nevin (1803-1886)

- Alexei Khomiakov (1804-1860)

- F. D. Maurice (1805-1872)

- David Friedrich Strauss (1808-1874)

- Isaak August Dorner (1809-1884)

- Pope Leo XIII (1810-1903)

- Heinrich Schmid (1811-1885)

- St. Theophan the Recluse (1815-1894)

- J. C. Ryle (1816-1900)

- Philip Schaff (1819-1893)

- Heinrich Heppe (1820-1879)

- Albrecht Ritschl (1822-1889)

- John of Kronstadt (1829-1909)

- Abraham Kuyper (1837-1920)

- B. B. Warfield (1851-1921)

- Vladimir Solovyov (1853-1900)

- Herman Bavinck (1854-1921)

- Ernst Troeltsch (1865-1923)

- St. Thérèse of Lisieux (1873-1897)

- Evagrius Ponticus

- The Cloud of Unknowing

- Theologia Germanica

- Francisco de Vitoria

- Jose de Acosta

- Gerard Winstanley

- Blaise Pascal

- Samuel Taylor Coleridge

- David

Walker

- Søren Kierkegaard

- Rauschenbusch

- Alcuin of York

- Rabanus Maurus

- Paschasius Radbertus

- Cassiodorus

- G. W. F. Hegel

- George MacDonald

- Ignaz von Döllinger

- Tobias Beck

- Adolf von Harnack

- Giovanni Perrone

- Franz Overbeck

- August Vilmar

- Jacques-Bénigne Bossuet

- Léon Bloy

Joseph Ratzinger on divine providence and the divided church

Twitter, Twitter, Twitter

An update

A very special episode of Daniel Tiger's Neighborhood

New essay published: “Be Fearful as Christ Was Fearful"

Over at Mere Orthodoxy, Jake was kind enough to publish a reflection I wrote on life in a pandemic. I actually wrote it all the way back in March, just as Covid was ramping up, when there were all kinds of calls from Christian writers, pastors, and thinkers to "not be afraid" or to be "free from fear." I use St. Maximus to discuss the role of fear in the Christian life, rooted in the presence of natural fear in the life of Christ. It's called "Be Fearful as Christ Was Fearful," and here's a taste of what I'm up to:

In other words, what we see in the Garden is not for show. It is not fantasy or fiction. Christ, because he is truly and naturally human, fears death the way any bodily creature might: for to be destroyed is not good, does not belong to an unfallen world. His humanity recoils from the prospect of the passion, not out of lack of trust in the Father or uncertainty in his vocation, but because he is like unto us in every respect apart from sin. As God with us, he is one of us. And it is only human to shrink before death, even death on a cross.

But Maximus wants us to see that that is not the end of the story, because Christ’s solidarity with us is always redemptive, and so it is here, too. His fear is part of his saving work in that it is exemplary for us. For, far from obstructing his obedience to God, Christ’s natural fear becomes the occasion for it. 'Not my will but thine' is the cry of a heart faithful to God in the presence of fear, not in its absence. It is the cry of courage, which is the virtue that knows the right thing to do, and wills to do it, when disavowal of fear would mean self-deception or recklessness. In this Jesus is our pioneer, the trailblazer of truly human courage, precisely in that moment when fearlessness would be foolish. For the will of the Lord outbids even our rational fears.

In this way, Maximus helps us to see what Christian fear might mean. All of Christ’s action is our instruction, as Aquinas says. Here too: we live as Christ lived, die as he died, suffer as he suffered, fear as he feared. If we are to grieve as those with hope, but still to grieve, so are we to fear as those with faith, but still to fear.